by Rachel Cross

Rachel Cross is a PhD candidate at Cardiff University whose area of research is Victorian illustrated songs. Her work investigates how the intersections between the three media of illustration, text and music reveal new insight into key issues of the Victorian period. She started her journey to this fascinating topic through music; initially studying piano, strings, and the theory of music, she gained diplomas in piano teaching and in the theory and criticism of music. Going on to study English at undergraduate and master’s levels, she focused particularly on the interrelations between text and illustration. She teaches about the relationships between text and illustration to undergraduates and has spoken about Victorian illustrated songs at several symposiums and conferences.

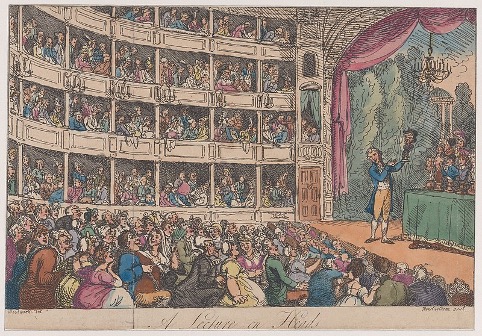

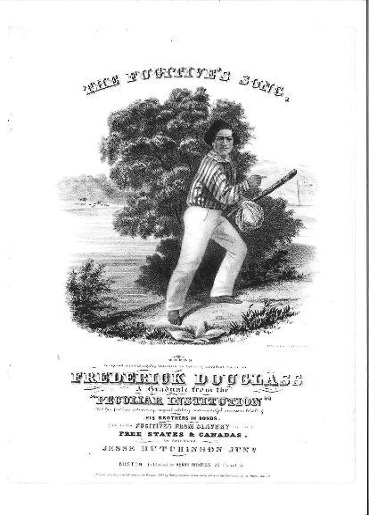

Illustrated songs were pervasive in the print culture of the nineteenth century: it is estimated that between 80,000 and 100,000 pictorial music titles were published in England between 1820 and 1885 alone. (1) They were popular in both America and Britain and were to become even more widespread with the rise of vaudeville (in the States) and music hall (in Britain) towards the end of the century. American and British songs traversed the Atlantic, bought largely by bourgeois families for domestic musical entertainment. The distinctive blend of the three art forms of text, music and illustration in one publication offers opportunity for an exciting tripartite view of nineteenth-century Western life. Examining intersections between presentations in these three media, this blog focuses on how an American antislavery song reveals nineteenth-century perceptions of race and nation. Its illustrated cover (see figure 2) depicts the fugitive whilst on the run, dramatically picturing the plight of the runaway. However, whilst the illustration shows the famous runaway, Frederick Douglass, it, and the song’s lyrics and music, also include other allusions which complicate the reading of ‘The Fugitive’s Song’ as connected with the antislavery mission.

Figure 1: Slavery Abolition Act, 1833. Photo credit: Wreford Miller, ‘Abolition’ by Wreford is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

After slavery in British lands was abolished in 1833 (see figure 1), American abolitionists campaigned with likeminded Britons to end slavery in America. The fight against slavery adopted a multimedia approach. Printed matter provided the main impetus for the abolition movement to spread its antislavery message and slave narratives and poetry were also augmented by songs and performances in both America and Britain. ‘The Fugitive’s Song,’ (see cover, figure 2) was published in Boston in 1845. Massachusetts was a centre for the abolition movement in the nineteenth century and Boston was a hub for early American music publishing. In May 1845, Frederick Douglass also published his critically acclaimed autobiography in Boston, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. Publication of this song, in tandem with Douglass’s book, is testament to the abolitionists’ multimedia crusade. However, I argue that this song also revealingly functions as a serenade to the ‘enlightened’ Northern states of America.

Douglass escaped slavery in 1838, subsequently becoming a famous antislavery campaigner in both the States and Britain. The popularity of slave narratives meant that many people were familiar with Douglass’s story. Frederick Law Olmsted, in his A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States (1856), even asserted that Northern views on slavery were constructed from the reading of slave narratives. (2) Whilst it is dedicated to Douglass, ‘The Fugitive’s Song’ was, however, like most antislavery matter, produced by a team of white people. The words are by Jesse Hutchinson Junior, with the music by J. M. White, and the cover illustration by the engraver and lithographer E. W. Bouvé. Initially testifying to the power of abolition songs, Douglass himself stated:

I especially have a reason to feel a grateful interest in the whole Hutchinson family ̶ for you have sung the yokes from the necks and the fetters from the limbs of my race. (3)

Indeed, as vehement abolitionists and members of the Anti-Slavery Society, the Hutchinson family used the power of music in the Northern fight against slavery in the 1840s and 1850s. (4) Scott Gac contends that, ‘Starting in 1841, the Hutchinsons transformed themselves from backwoods, church-trained musicians to the most popular musical family in America’. (5) By the end of the Civil War, Douglass had, however, changed his opinion about white involvement, declaring, ‘Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us’. (6) Indeed, African American disillusionment followed emancipation, these sentiments contrasting sharply with the hopefulness of earlier abolitionism.

The text, music, and image of ‘The Fugitive’s Song’, although created by different people, work together to supposedly produce an authentic version of slavery. Douglass’s story is used to personalise the plight of the enslaved and enable performers to feel an emotional connection and moral obligation. Yet, all three media also represent Douglass’s freedom as largely due to the magnanimity of the Northern states. The lyrics use religious lexis: indeed, many antislavery songs like this were sung in churches. The song is focalised through Douglass, and he affirms his faith in God in the first verse:

From my youth I have vow’d in my God to rely

And despite the oppressor gain Freedom or die.

Yet, the lyrics also use nationalistic vocabulary. Despite the fugitive’s apparent reliance on heavenly help, it is New England’s ‘stern voice’ that has the power to protect and shelter the runaway, expressed in the third verse:

New England! New England! thrice blessed and free,

The poor hunted slave finds a shelter in thee,

Where no bloodthirsty hounds ever dare on his track;

At thy stern voice, New England! the mountains fall back!

Indeed, the voice seems to have divine authority, as the fourth verse continues:

That voice shall roll on, ’mong the hills of the North,

In murmurs more loud ’till its thunders break forth;

On the wings of the wind shall its deep echoes fly,

Swift as Lightning above, from sky e’en to sky;

Nor Charters nor Unions its mandates shall choke,

’Twill cry in God’s Name, ‘Go Break every Yoke’

Like the tempests of Heaven, shaking mountain and sea,

Shall the North tell the South, ‘Let the Bondmen go free!’

Lauding the Northern states in this way is reminiscent of the lyrics of national anthems of the day. Emphasising the North’s progressive climate where ‘no bloodthirsty hounds’ pursue the runaway suggests its ideals are far from the barbarism of the South. This sense of nationalistic pride is carried further in the final verse:

Oh! then shall Columbia’s proud flag be unfurl’d

The glory of Freemen, and pride of the World,

While Earth’s struggling millions point hither in glee,

‘To the Land of the Brave, and the Home of the Free!

’The words ‘Columbia’s proud flag’ seem to reference the American patriotic song ‘Hail, Columbia’. (7) Likewise, the final line of ‘The Fugitive’s Song’: ‘To the Land of the Brave, and the Home of the Free!’, has parallels in Francis Scott Key’s 1814 poem (which became the lyrics of the American national anthem):

Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet waveO’er the land of the free and the home of the brave? (8)

Despite attempting to create a slave narrative-like feel, therefore, the lyrics are firmly positioned within the tradition of Western religious and nationalistic poetry.

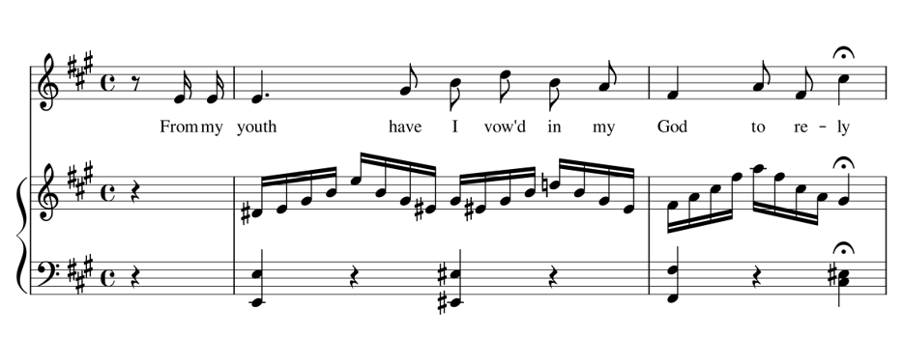

In a similar way, the music is unashamedly Euro-American, having a diatonic melody (based on the Western scale) and a steady march-like pulse. The melody’s triadic motifs (centred around an arpeggio) sound fanfare-like (see figure 3).

These patterns also have connotations of national anthems: the style of the music here corresponds with the patriotic lyrics. National anthems were becoming more significant in the increasingly nationalistic nineteenth century and they often used fanfare-like motifs. (9) As F. Gunther Eyck writes in his study of national anthems, they were based on concepts from the romantic movement, including ‘the search for symbols, religious revivalism, and an emotional rather than a rational approach to contemporary issues’. (10) ‘The Fugitive’s Song’, like national anthems of the day, encouraged an emotional, and indeed religious, engagement, ostensibly in the fight against slavery, but also in nationalistic feeling. Just as the words’ intertextual references to other patriotic verse incited the listener or singer to a sense of patriotic zeal, so musical symbols, or leitmotifs, such as fanfare-like calls, allowed association with a nation’s triumphant battle fanfares. (11) This interaction with other snippets of music works in a similar way to the interpictoriality of imagery and the intertextuality of texts. As in art and literature where viewers and readers see references to other works, so also in music, aural memory inescapably draws allusions to other music, the listener (or performer) making connections outside of the song itself. This is therefore a musical version of the interplay that illustration has with other images. Julia Thomas, writing on illustration and its relationships with text and other imagery, terms this ‘affillustration’, where illustration:

makes meanings not just in its (conscious and unconscious) references to other illustrations, but also in the groupings and clusters it generates, the ‘networks’ that exist within and across the boundaries of the illustrated text. (12)

Music, therefore, like illustration, is a ‘social genre’: both the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and ‘La Marseillaise’ have similar triadic melodic motifs allowing listeners and performers to make connections between them and ‘The Fugitive’s Song’. The music’s martial 4/4 time also aligns it with other nationalistic songs, many of which were used during battles to rouse soldiers in patriotic fervour. Recognisable patterns in rhythms and melodies meant that they could be picked up easily and sung together. Indeed, as sociomusicologist Simon Frith points out, music is uniquely able to create a feeling of ‘spontaneous collective identity’ and ‘personally felt patriotism’. (13) Using such familiar methods in the music ̶ and lyrics ̶ of ‘The Fugitive’s Song’ encouraged engagement and a feeling of camaraderie which was a feature of patriotic music. As antislavery ideals became an identifying feature of the Northern states prior to (and during) the Civil War, these musical and language techniques furthered the sense of the North as synonymous with freedom for all.

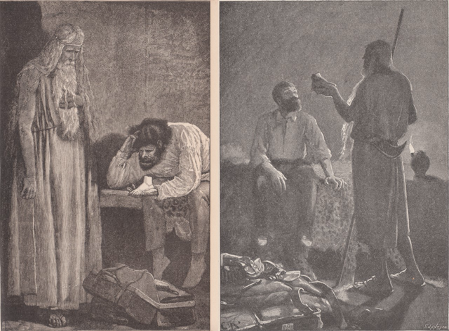

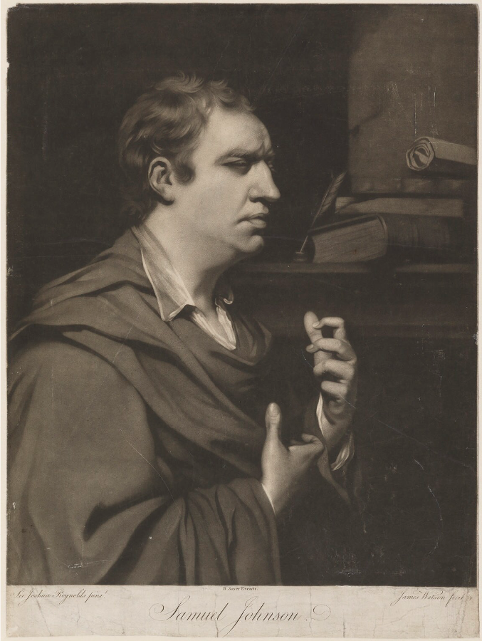

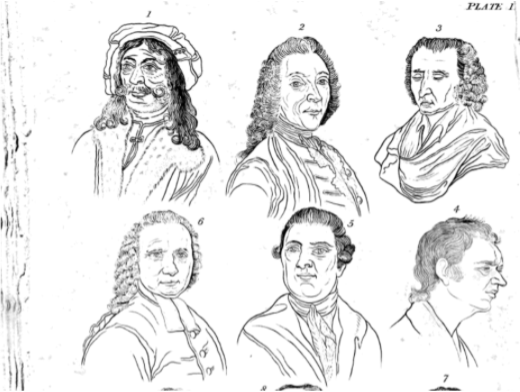

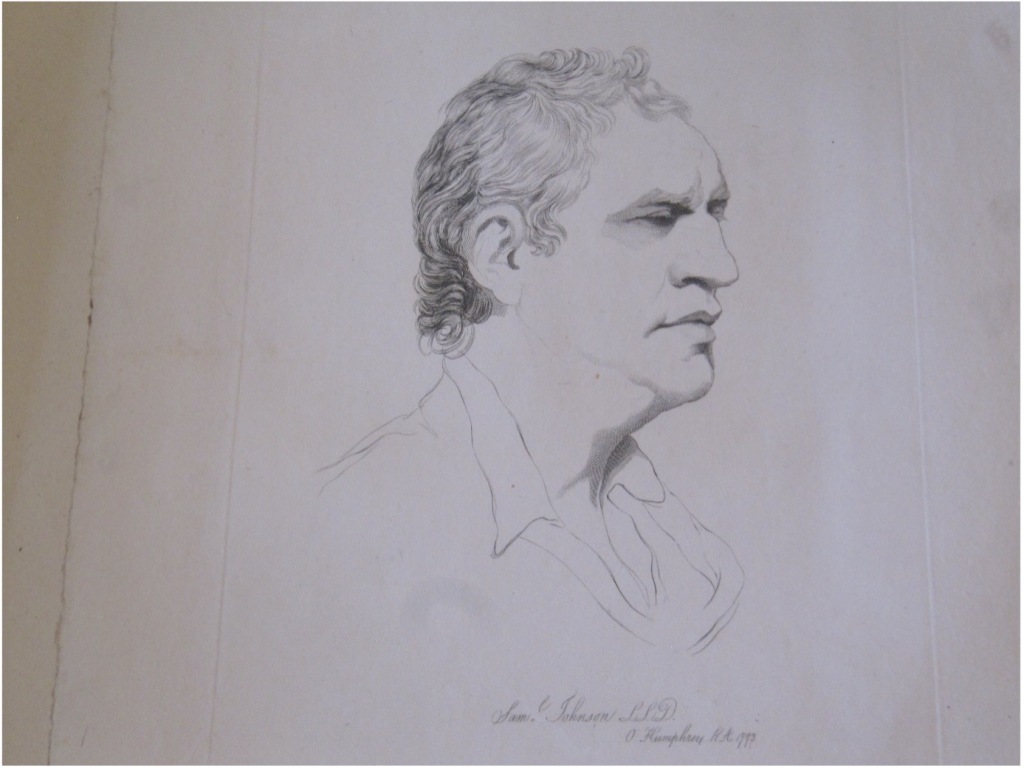

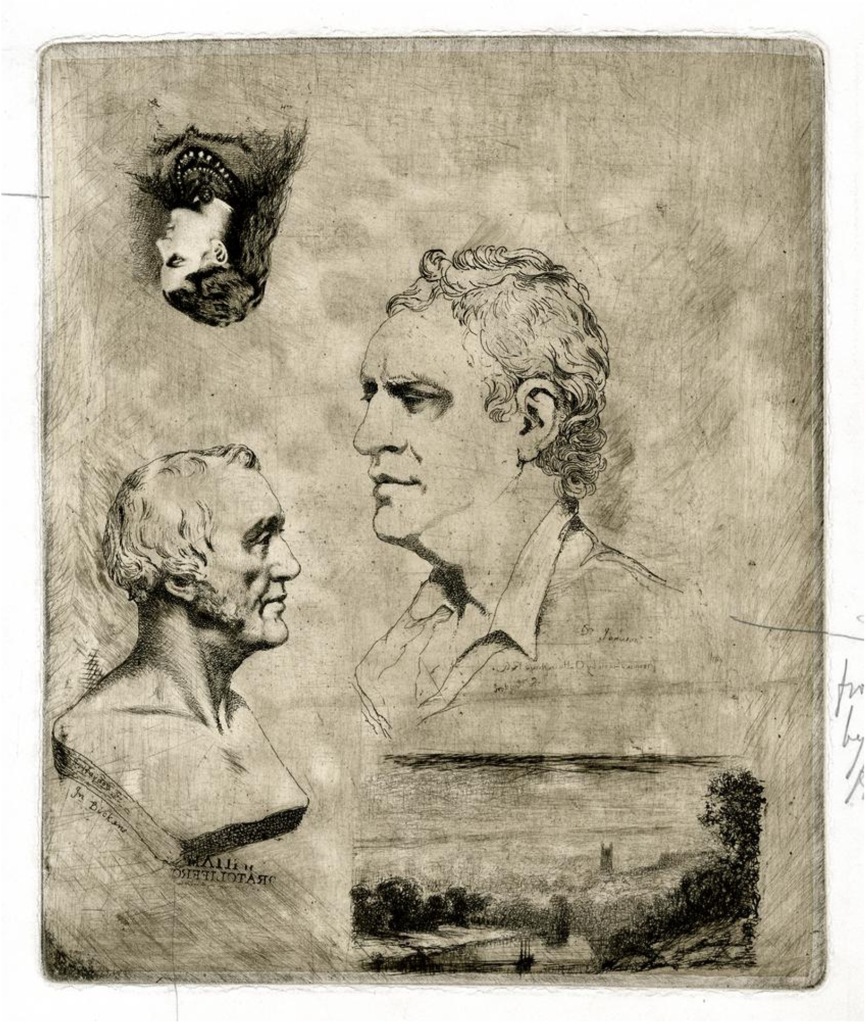

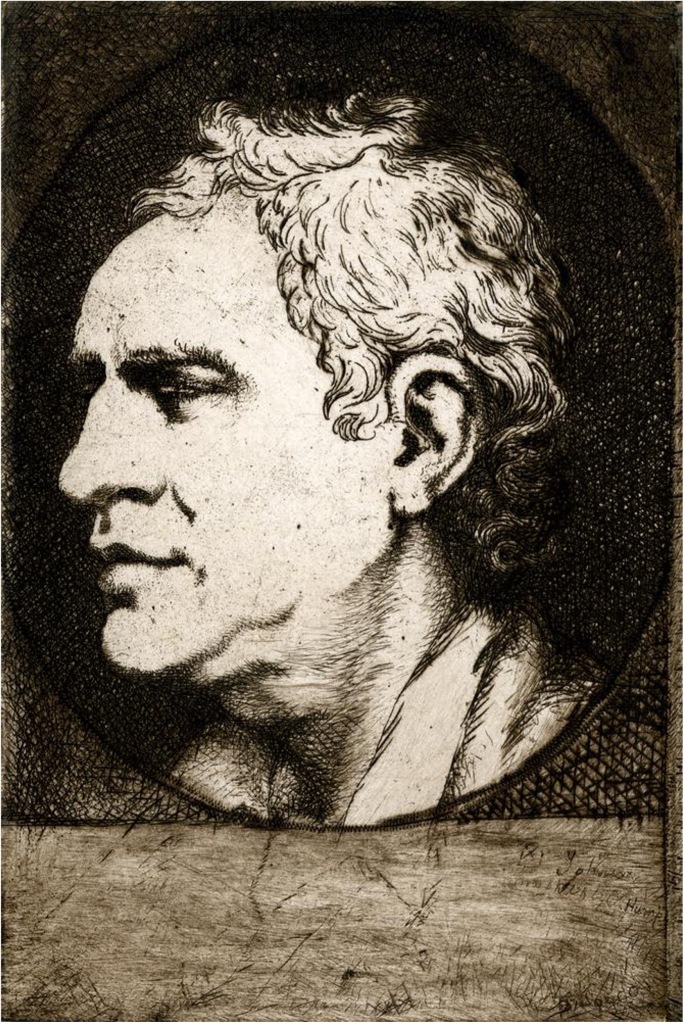

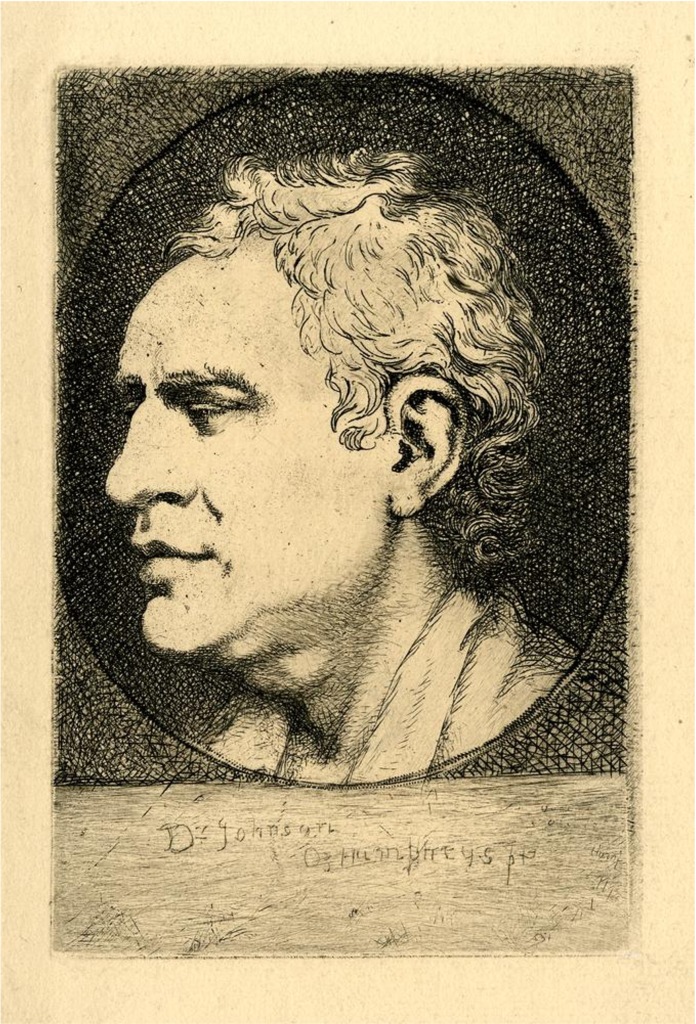

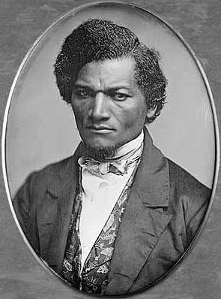

The cover illustration uses Douglass’s figure to further associate the song with him and his antislavery mission. As the most photographed man of the nineteenth century, Douglass would have been recognisable by many (see figure 4). (14, 15)

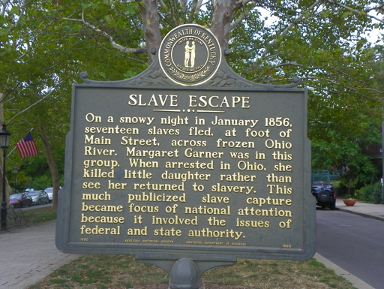

Indeed, his depiction as face on to the viewer, allows immediate identification from his features and distinctive hair. The cover also references Douglass’s story: the Ohio River behind Douglass provides a physical symbol of the separation of North and South. The frozen Ohio River was famously crossed by Margaret Garner and her fellow fugitives in 1856 (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Memorial Marker, Covington, Kentucky. Photo credit: J. Stephen Conn, ‘Slave Escape Historical Marker’ by J. Stephen Conn is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The sign indicating New England is also mirrored by Douglass’s pointing finger, referencing his escape from Maryland to Massachusetts. (17)

Crossing the Ohio River symbolised an escape to freedom for many enslaved people. The illustration also therefore seeks to emulate a slave narrative whilst simultaneously glorifying the Northern states. Pictorial references to New England here serve to substantiate the song as an accurate account of Douglass’s experiences, whilst also underpinning the patriotism of the lyrics.

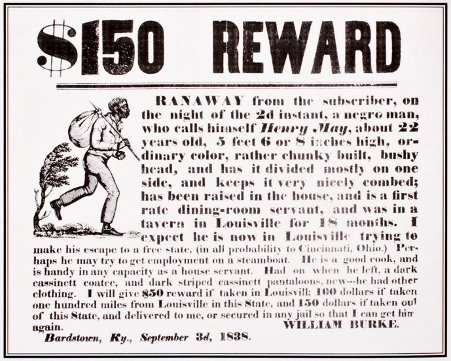

Yet, Douglass’s pose has a more complex frame of reference with a dual heritage of North and South. It is similar to the figures of fugitives on the many Southern posters and press adverts for runaways, such as this one from the same year as Douglass’s escape, 1838 (figure 6). However, this allusion does not undercut the patriotism of the lyrics and music. Northern American arrogation and adaptation of this image shows the North’s moral distance from the South, ironically using a Southern image to expose the inhumanity of the South. Indeed, Marcus Wood, who has written extensively on representations of black people in visual culture, claims that not only was it used in Southern runaway advertisements, but the image was also appropriated for use in slave narratives and early British abolitionist literature. (18) Similarly, American and African American literature specialist, Martha Cutter notes how antislavery illustrations were reworked and reused in other abolitionist literature, repurposing them as emotive antislavery imagery. (19) Here, the martyrologising of a Southern motif reveals the polysemous nature of imagery and how readings of illustrations could be adapted so that they functioned in diverse ways in different circumstances. (20) Indeed, such affillustrative references to both Southern imagery and Douglass’s story would have allowed purchasers of the song to divine its significance as part of Douglass’s heritage. Yet, such understanding is complicated by the cover’s specific geographic symbols, implying rather that it was not who escaped but where he escaped to that is important.

‘The Fugitive’s Song’ was therefore written to appeal to a predominantly white audience, presenting a whitened version of Douglass’s story. Whilst the three media apparently portray an authentic account, requisitioning Douglass as figurehead is evidence of the somewhat peremptory nature of nineteenth-century Western advocacy for the voiceless African American. Perhaps this is an early example of the ‘mischief’ of Douglass’s later complaint. Indeed, reusing nationalistic motifs in all three media that underline the North’s importance in Douglass’s escape seem somewhat self-congratulatory. The three media of this song together reveal some of the complexities of nineteenth-century attitudes about slavery as connected with race and the significance of patriotism in American abolitionism. Therefore, studying the illustrations of illustrated songs in connection with their music and lyrics opens up new channels of dialogue around how issues, particularly difficult ones such as slavery, were, and are, negotiated.

(1) A. Hyatt King, ‘English pictorial music title-pages 1820-1885: Their style, evolution, and importance’, The Library, 4 (1950): pp. 262-272, p. 270.

(2) Charles H. Nichols, ‘Who Read the Slave Narratives?’ The Phylon Quarterly, 20: 2 (1959): pp.149–162, p. 153.

(3) Jesse’s brother John also sang ‘The Fugitive’s Song’ at Douglass’s funeral in 1895. See ‘Washington Talk Briefing: The Hutchinson Family’, The New York Times, 21 September 1987, p. 8. <https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/21/us/washington-talk-briefing-hutchinson-family.html> [accessed 23 January 2019].

(4) ‘Songs Against Slavery Used as Tool for Abolition’, Voice of America, 13 January 2014 <https://www.voanews.com/a/songs-against-slavery-tool-for-abolition/1829393.html> [accessed 24 January 2019]. They also toured with the black Luca family although this was sometimes frowned upon, see Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History (1971; New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 1997), p. 107.

(5) Scott Gac, Singing for Freedom: The Hutchinson Family Singers and the Nineteenth-Century Culture of Reform (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), p.4.

(6) Frederick Douglass, ‘What the Black Man Wants’, Speech at the Annual Meeting of the Massachusetts Antislavery Society in Boston, April 1865 http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/africam/afspfdat.html [accessed 30 May 2019].

(7) These lyrics were written in 1798 by Joseph Hopkinson. The repeated references to freedom (which applied to freedom from the British) are particularly multivalent.

(8) The poem, which was later set to John Stafford Smith’s melody, was adopted as the national anthem for the United States on 15 April 1929. ‘The Designation of the “Star-Spangled Banner”’, 3 March 1931, History, Art and Archives: United States House of Representatives https://history.house.gov/Historical-Highlights/1901-1950/The-designation-of-the-%E2%80%9CStar-Spangled-Banner%E2%80%9D/#:~:text=The%20Congressman%20passed%20away%20before,introduced%20to%20the%20House%2C%20H.R. [accessed 07 February 2022].

(9) See Paul Nettl, trans. by Alexander Gode, National Anthems (1952; New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing, 1967).

(10) F. Gunther Eyck, The Voice of Nations: European National Anthems and Their Authors (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), pp.xiii-xiv.

(11) A leitmotif is a recurrent musical theme associated with a particular idea, place or character. Eyck makes the point that in ‘almost every case, musical composition postdated the creation of the stanzas’, suggesting that composers used word painting and implying that this developed into the use of symbols to paint lyrics that were similar in many types of nationalistic verse writing. Eyck, The Voice of Nations, p.xv.

(12 ) Julia Thomas, Nineteenth-Century Illustration and the Digital: Studies in Word and Image (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), p.97.

(13) Simon Frith, ‘Towards an aesthetic of popular music’ in Richard Leppert and Susan McClary (eds.), Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance and Reception (1987; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989) p.141.

(14) Autumn Haag, University of Rochester’s Special Collections librarian, describes Douglass as also ‘really aware of his self-image’ in Daniel J. Kushner, ‘Rare sheet music inspired by Frederick Douglass obtained by UR’ https://rocdouglass.com/2018/08/11/rare-sheet-music-inspired-by-frederick-douglass-obtained-by-ur/ [accessed 25 January 2019].

(15) For more on this, see John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, Celeste-Marie Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2015).

(16) Daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Douglass#/media/File:Frederick_Douglass_by_Samuel_J_Miller,_1847-52.jpg [accessed 30 March 2022].

(17) The Ohio River was considered the extension of the division between North and South, the Mason-Dixon line, here separating Maryland in the South and Pennsylvania in the North.

(18) Marcus Wood, Blind Memory: Visual Representations of slavery in England and America 1780 – 1865 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), pp.78-142.

(19) Cutter charts the reworking of an image of a white man whipping a slave woman and child originally from the American Antislavery Almanac for Henry Bibb’s slave narrative, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb in 1849, for example in Martha J. Cutter, The Illustrated Slave: Empathy, Graphic Narrative, and the Visual Culture of the Transatlantic Abolition Movement, 1800-1952 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017), p.167.

(20) Copyright laws were principally to protect literary works rather than this type of imagery, Copyright Timeline: A History of Copyright in the United States http://www.arl.org/focus-areas/copyright-ip/2486-copyright-timeline#.W5uTHuhKjIU [accessed 14 September 2018].