Rose Roberto

Rose Roberto is a part-time Lecturer in the School of Humanities and Teaching Resources Librarian at Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln, UK. Her masters in library and information science is from the University of California, Los Angeles, and her PhD in history of the book is from the University of Reading. Her current research examines the intersection of visual culture and educational publishing, and the hidden histories related to race, gender and class embedded in the material culture of the transnational book trade during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She was series editor for the Art Researches’ Guides ’to different cities in the UK and Ireland (2011–2017), and a contributor to the award-winning Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, Vol. 2 (Finkelstein, 2020), and Circulation and Control: Artistic Culture and Intellectual Property in the Nineteenth Century (Delamaire and Slauter, 2021). She is a Fellow of the HEA.

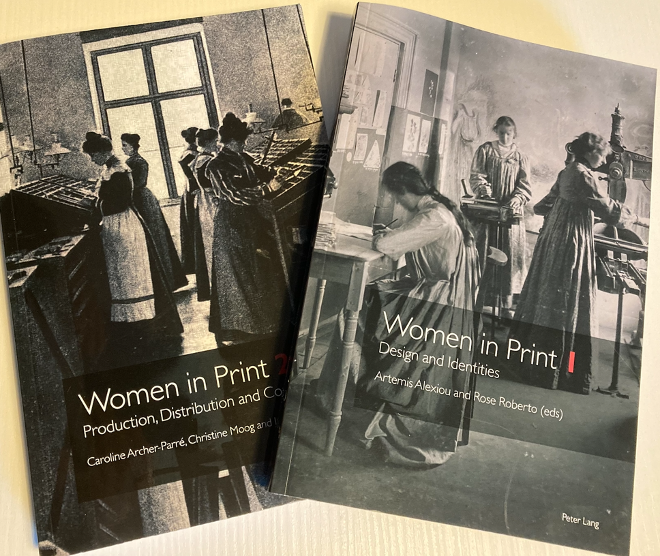

Back in September 2018, when I should have been concentrating on finalizing my PhD thesis due two weeks later, I participated in a conference held at the University of Birmingham entitled, ‘Women in Print.’ The event saw scholars present research on historical women and their impact on the printing and publishing trades, as well as on print culture in general. Unfortunately, the majority of women we discussed had names that are not well-known today because subsequent narratives of them in the historical record either neglected and undervalued their work, or deliberately obscured them. Most of us who attended this conference were impressed by the level of scholarship that had been conducted, and plans were made the following year to publish Women in Print, a collection of essays in two related volumes. In 2022, these volumes were issued as part of the ‘Printing History and Culture’ series published by Peter Lang.

Women in Print 2: Production, Distribution and Consumption and Women in Print 1: Design and Identities

The first volume co-edited by Artemis Alexiou (York St John University) and myself, will be of particular interest for members of the Romantic Illustration Network. Women in Print 1: Design and Identities contains eleven chapters incorporating case studies of design aspects of a printed work, or more broadly about design issues related to the business of publishing. It also contains chapters focused on specific individuals and their career as female artists, compositors, editors, engravers, photographers, printers, publishers, scribes, stationers, typesetters, widows-in-business, and writers. It offers an examination of women as active participants and contributors in the many and varied aspects of design and print culture, including the production of illustrations, typefaces, periodical layouts, photographic prints and bound works. Several of the women profiled in this volume lived and worked during the Romantic period, roughly between 1750 and 1850. This volume covers the visual material that they produced.

The second related volume, Women in Print 2: Production, Distribution and Consumption contains chapters covering professional relationships between two or more women or a business network in which aspects of their roles in production, distribution and consumption of the printing trade are explored and further analysed. It was co-edited by Caroline Archer-Parré of Birmingham City University and Christine Moog of the Parsons School of Design in New York. Series editor John Hinks is also credited because of his work organising the conference and guiding the manuscripts through delays, mainly caused by two years of a world-wide pandemic, to publication.

My own chapter, ‘Working Women: Female Contributors to Chambers’s Encyclopaedia’ appears as Chapter 6 in this related volume. My search for women authors through time and through archives (spanning Philadelphia to Edinburgh, and London to Manchester) led me to discover some twenty-five female encyclopaedia contributors. As well as considering these women, my chapter traces the evolving process throughout the 1800s whereby the status of women as professionals in various fields developed. Like museums, encyclopaedia are heavily curated through a selection of topics, encapsulating a specific time, place and world-view. They also reflect evidence of particular narratives of history, science and culture. Since the Scottish publishing firm, W. & R. Chambers was significant, their edited works and attitudes are good indicators of the status quo for publishers of the time.

Various volumes from both the first and second editions of Chambers’s Encyclopaedia at Chetham’s Library, Manchester. Photo by Rose Roberto.

Although I could not cover all twenty-five contributors in my chapter, ‘Working Women’ does highlight the writings of six authors found in different editions of Chambers’s Encyclopaedia, first published between 1859 to 1868, and 1888 through 1892. Three encyclopaedia entry authors, Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847-1929), and Carrie Burnham Kilgore (1838-1909), are well-known in their fields of nursing and mathematics, and as advocates for women’s rights and women’s higher education, respectively. Three other writers are from an earlier period and are less-known, but made a living from their writing. Isa Craig Knox (1831-1903) is considered a late, minor Romantic period poet; Lucy Cumming Smith (1818-1881) and Elise Otté (1818-1903) both translated history and literature and were published authors. My chapter briefly summarises the lives of these six women and their relationship with publishers, notably the relationship with the Chambers publishing firm. I highlight how they were commissioned to write encyclopaedia entries and contrast the fact that Craig Knox, Cumming Smith, and Otté were hired more on account of their writing and translating skills, whereas Garrett Fawcett, Kilgore and Nightingale were commissioned for their subject expertise. Clearly both groups of women were all capable writers and subject experts, but their commissions expose how publishers had different priorities and criteria with regards to employing women at the beginning of the nineteenth century and towards its close.

The chapter also reflects my fascination with the social networks each woman developed throughout her life. In the case of Nightingale, her professional relationship with Sir Douglas Galton (1822-1899) was the reason that W. & R. Chambers had contact with her. There are numerous stories of women and their work in both volumes of Women in Print. The volumes provide a fresh perspective on well and lesser-known women, spotlighting their individual involvement with the printing and publishing trade. Volume one makes an effort to discuss gender, class, and sexuality as a means of expanding knowledge and understanding of intersectional design practices, whilst volume two’s essays focus on women involved in on the business side of publishing, namely as producers and distributors operating through extensive business networks. It also examines women’s consumption of printed material.

Together, these collections of essays show that women were always present and have been actively involved in numerous fields across print culture. While most histories until the last forty to fifty years often treat women’s histories ‘as outstanding anomalies’ in cultural and professional fields dominated by men, the aim of the scholarship here is to approach the lives of women – and writing about their lives – as part of a process which reveals complex individual histories. (1) We hope you take the opportunity to read Women in Print and will encourage your library to purchase the volumes.

https://www.peterlang.com/document/1296871

The second blog post in this series is by Hannah Lyons, Assistant Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich. Hannah shares excerpts from her chapter on the print and publishing life of Letitia Byrne, another wonderful contribution to Women In Print Volume 1. The piece can be read here: https://romanticillustrationnetwork.com/2023/01/25/women-printmakers-in-the-eighteenth-century-exploring-the-print-and-publishing-life-of-letitia-byrne-in-women-in-print/

(1) Alexiou and Roberto, “Introduction” in Women In Print 1 (2022, p.3)