Caroline’s Death and an Unpublished George Cruikshank Image

Ian Haywood, University of Roehampton, London

Queen Caroline’s death was as controversial as her life. After more than a year of political upheaval and unprecedented media attention, Caroline passed away on 7 August 1821, aged 53. The medical cause of death was a digestive blockage, but Caroline’s followers saw things differently. In their eyes, she had died of a broken heart, the victim of a government-led campaign of persecution and vilification. She was the ‘injured’ queen to the very end. Only weeks earlier, on 19 July, Caroline had been barred from attending George IV’s coronation in Westminster Abbey, and this definitively un-queenlike humiliation was widely believed to have hastened her rapid demise, especially as she was already a weakened figure. The coronation debacle was the climax of a sustained propaganda counter-offensive which followed her stunning triumph in late 1820 (see the ‘November 1820’ blog). When Caroline failed to seize the political moment and bring the government down, her enemies made a concerted effort to shift public opinion against her by dwelling on eye-catching flaws: her sex life, her corrupt aristocratic lifestyle, and her departure from the moral codes of respectable femininity and the correct standards of royal conduct. As anti-Caroline caricatures flooded the market, her support wavered further when she accepted an increased allowance of £50,000, the same amount she had symbolically refused when she returned to England the previous year (see the ‘June 1820’ blog). But her death was an immediate and sensational rallying point for her supporters, an opportunity to retake the moral high ground and to dominate the media with tributes, commemorations, and accusations of foul play. The violence that erupted at Caroline’s funeral only confirmed the malign role of the government and its petty determination to deny her royal reputation and rights. The public outrage at this neo-Peterloo atrocity led to some memorable caricatures, including a striking unpublished design by George Cruikshank, which shows popular justice being meted out to a military officer (Figure 1).

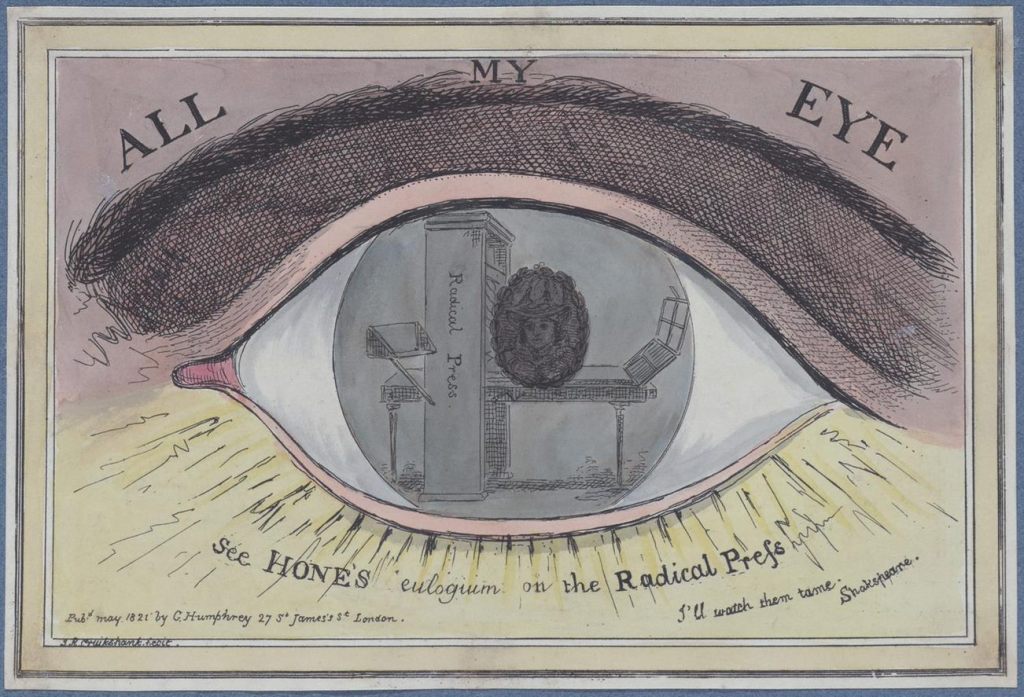

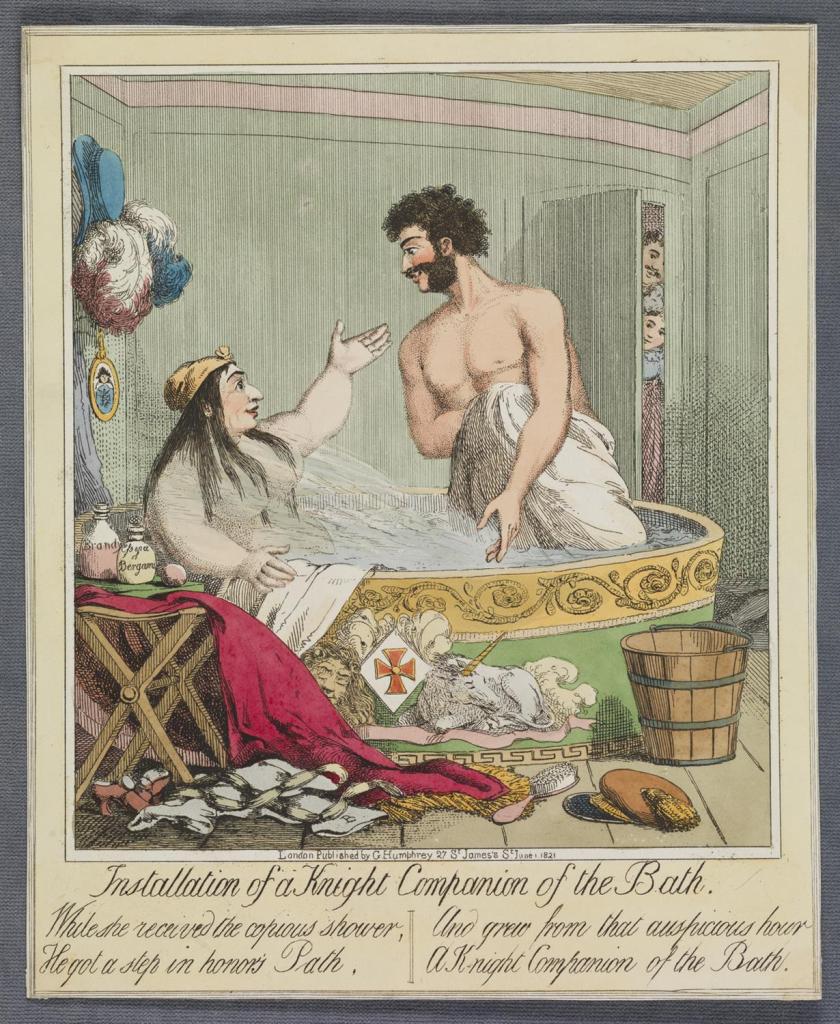

To understand and appreciate this image more fully, we need to retrace our steps and look more closely at the explosion of print culture which followed Caroline’s death. As already noted, this was the moment to reverse the tide of negative reportage and visual propaganda which had dominated 1821 up to that point. In this loyalist counter-narrative, ‘Caroline the Curst’[1] was the antithesis of the indomitable, rebellious heroine of the radical imagination. Instead of Boadicea, she was Messalina, the infamous meretrix augusta or ‘imperial whore’ of Juvenal’s Sixth Satire, an aristocratic Roman matron who supposedly slept with lower-class men to satisfy her insatiable sexual appetite.[2] According to one verse satire entitled Messalina, Caroline’s trial (which technically had found her guilty of adultery, though only by the slimmest of margins) ‘pronounc’d the queen / Had clearly a low trollop been’[3], a slur that evoked memories of the virulent lampooning of Caroline’s ‘butcher-kissing’ predecessor Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, another upper-class woman who dared to mix in public politics.[4] The accusation of demeaning promiscuity was also a metaphor for the greater offence of courting public opinion. Caroline had willingly turned herself into an ‘exhibit’ for public consumption, ‘courting the favour of a populace, whose breath is bought and sold’ instead of rededicating herself to her husband.[5] She was a triple offender, exposing her royal body indiscriminately to the disreputable gaze of lovers, radical politicians, and the masses. This multiple prostitution of her image was the focus of a series of high-quality caricatures published by George Humphrey in early 1821.[6]

Two examples of these prints are included here (Figures 2-3). The title of Installation of a Knight Companion of the Bath (Figure 2) puns on Caroline’s promotion of Bartolomeo Bergami from servant to personal assistant. The chivalric title Knight of the Bath was normally awarded for outstanding military or diplomatic service, and not – as in this case – for sexual gratification. This scene illustrates one of the alleged examples of adultery which were recounted in fulsome, often risible detail at Caroline’s trial. Instead of the purifying bathing ritual of the original chivalric Order, we witness a Rowlandsonian erotic frolic in which Bergami’s orgasmic ‘copious shower’ expresses the sheer joy and guilt-free abandon of their relationship. This is indeed damning visual evidence of ‘low trollop’ behaviour, but as so often in caricature the scene is also full of mischievous satirical traps. Caroline’s opponents might well have gloated over this bathtub tryst, but they were also forced to confront the voyeuristic basis of their pleasure. In the background there is a partially open door which shows two servants who are spying on the lovers, and while this device may signify the authenticity of the eye-witness accounts, it is also a reminder of the prurient gaze of scandal which made Caroline’s trial simultaneously titillating and distasteful. This tainted gaze contrasts with the openly affectionate eye contact of the two lovers, and this juxtaposition could imply that Caroline’s accusers are both jealous and resentful of her sexual independence and – as represented by the discarded clothing – her contempt for convention. Another object which defies social and moral norms is the miniature portrait of Bergami which is hanging on the wall behind her head and which she wears openly and unashamedly in other prints. For viewers today, these complexities make this image far more challenging and rewarding than first impressions might suggest.

The second example from the Humphreys series switches the satirical focus from private to public indiscretion. Grand Entrance to Bamboozl’em (Figure 3) is a parody of the spectacular processions and rallies which became such a feature of Caroline’s campaign, and which (as we shall see) also defined the conclusion of the controversy, though in an unexpected way. The intention of the print seems to be to undermine the memory of these gatherings by converting them into a cross between a pantomime and an impending riot, simultaneously laughable and threatening. Caroline is located appropriately at the centre of the scene and her appearance conveys these mixed messages of menace and ridiculousness: she rides an ass instead of a horse (a wry allusion to visual representations of her ‘public entry’ into Jerusalem in 1815), wears a very revealing ‘décolletée over-dress’[7] instead of modest and dignified attire, openly sports the Bergami locket, and on her head is a red cap of Liberty which also resembles the clown’s hat worn by her companion Alderman Wood – a far cry from their heroic stance in Robert Cruikshank’s The Secret Insult (1820), the print which heralded Caroline’s return to England (see ‘June 1820’ blog). According to the writing on her saddle-cloth and the text in the oval plate below the image, she is also Columbine and Mother Red Cap, two famous lower-class characters from popular culture. Columbine was the plucky and irreverent servant of commedia del arte and its derivative English pantomime, and Mother Red Cap was a legendary pub landlady and (in some versions of the story) a witch.[8]

These identities are no doubt intended to confirm Caroline’s ‘trollop’ misdemeanours and unforgiveable mingling with the hoi polloi, but they also evoke a rumbustious culture of popular performance and folk tradition which gives the print an engaging, populist and carnivalesque quality. The uplifting impression created by the vivid colours, festive atmosphere, multiculturalism (Caroline’s entourage includes a black man who could be her adopted servant Louges)[9] and conviviality (Bacchus is literally part of the crew), together with the transformation of central London into an amphitheatre of democratic spectacle, overpowers the negativity of the incendiary banners which recede into the right distance, and the ominous bolt of lightning on the horizon. The lively gaggle of reformers who are waiting to greet Caroline (including the Peterloo speaker Henry Hunt, who was still in jail) are not heavily caricatured. The lavish detail of the print, which contains dozens of well-drawn characters and many symbols, is also a tribute to the quality and efficacy of the Carolinite caricature campaign which had set such a high bar. This may be a vaudeville Caroline, but the effervescent and joyous emotion of the scene has an infectious and seductive energy.

As these examples show, the caricature assault on Caroline’s moral probity could not entirely eradicate her populist appeal as a woman of the people, and the constant parodying of her cause did, after all, keep her in the public eye. One way to view the king’s lavish coronation, which had been deferred for a whole year, is that it was an attempt to finally eclipse and derail the Caroline roadshow. The liberal and radical press responded by condemning the ostentatious expenditure, highlighting evidence of lacklustre popular support, and of course expressing outrage at the queen’s exclusion.[10] Just a few weeks later, Caroline’s death provided the perfect opportunity to upstage this cynical display of national pomp with the queen’s celestial coronation, a ‘Crown of Glory, / Where oppressors cannot come’.[11] She was now a true martyr who had died for her beliefs. Two phrases were on everyone’s lips: her dying words ‘They have destroyed me’ and the title ‘injured queen’, which was provocatively inscribed on her coffin. These and similar taglines populated the tributary merchandise that flooded the market at all social levels: poems, elegies, sermons, portraits, engraved medallions, hagiographies and broadsides. This was the final chance to set the record straight, and the greater the offence against her, the greater her moral and spiritual victory.

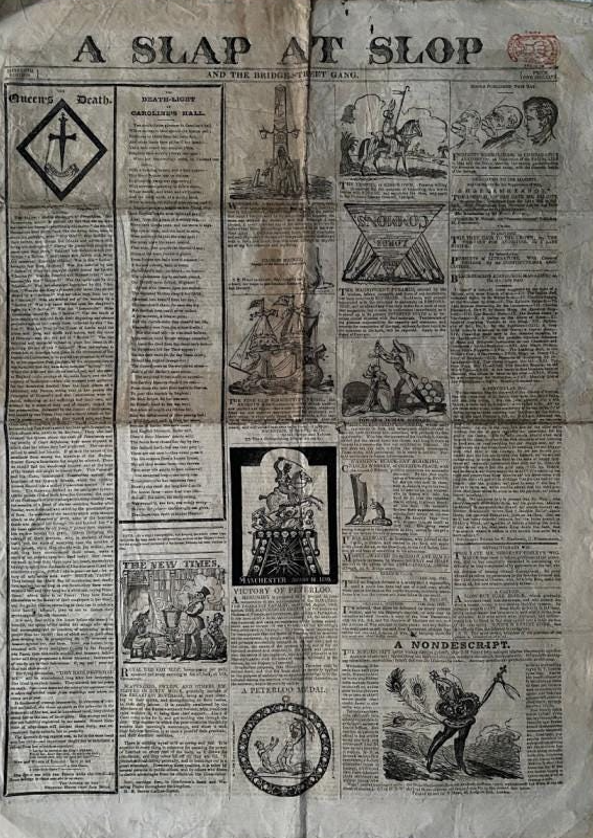

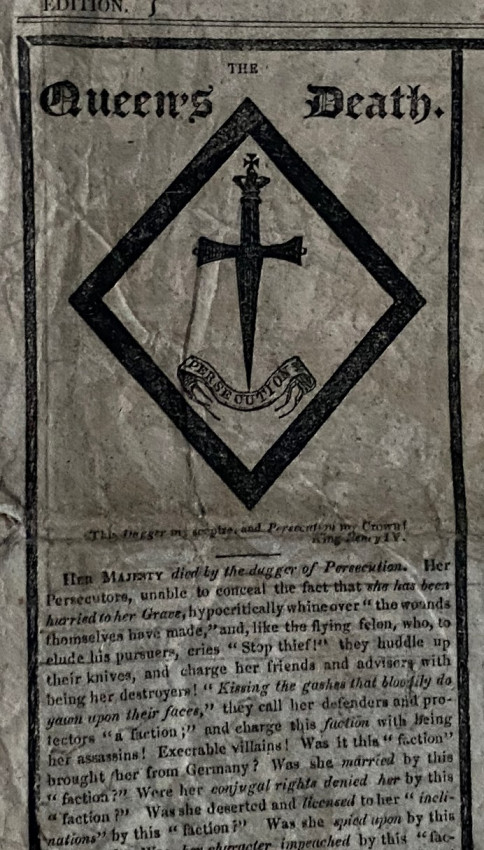

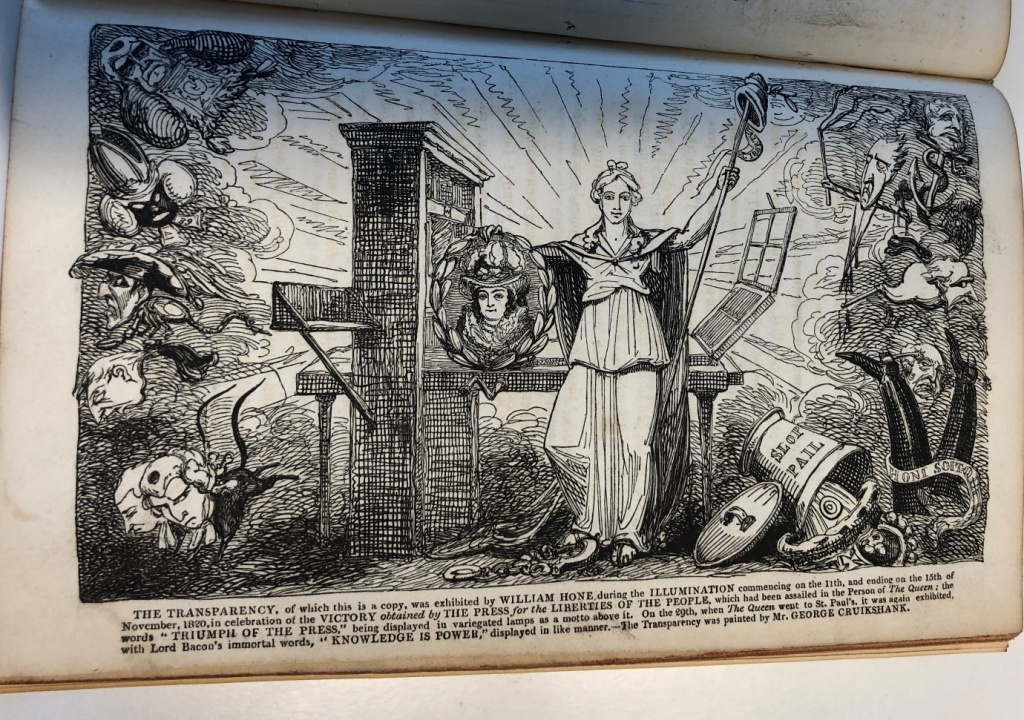

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most effective satirical response to Caroline’s death came from William Hone and George Cruikshank. The formidable duo lost no time in announcing the event on the front page of their highly successful satirical newspaper A Slap at Slop (Figure 4). With characteristically audacious visual and verbal flair, the conventional funerary hatchment is replaced with a dagger hovering over the bannered word ‘Persecution’ (Figure 5). The caption below modifies Falstaff’s lines from Act Two, Scene 4 of Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part One: ‘This chair shall be my state, this dagger my sceptre, and this cushion my crown’ becomes ‘This Dagger my sceptre, and Persecution my Crown!’ In the original scene, Falstaff is pretending to be Prince Hal’s father the king, so the allusion would be comic if it were not so tragic. The implication is that Caroline’s spouse still resembles the unreformed Hal rather than a responsible ruler, hence George’s callous treatment of his wife is likened to a Tudor-style judicial murder. This was satirical hyperbole, though George’s decision to visit Ireland rather than attend Caroline’s funeral was seen by many as confirming his inhumanity.[12] As the adjacent satirical woodcuts on the front page of Slap at Slop show, Caroline’s death coincided with the second anniversary of the Peterloo massacre. In the radical imagination, she became the latest victim of brutally repressive government.

The memory of Peterloo was never far away during the Caroline controversy, but no one could have predicted that her funeral procession on 14 August – just two days before the second anniversary – would actually turn into a mini-Peterloo. The violence was a spectacular demonstration of the continuing disagreements about her status and rights. As she herself declared on her death-bed, she was ‘Queen – and no queen’.[13] This ambiguity disfigured and defined both her life and her death. Denied a full state funeral, her followers stepped in to ensure that she was accorded a fittingly grand departure. However, a dispute arose concerning the route that the funeral procession could take through London on the way to Harwich, where her coffin would embark for Germany.[14] The authorities insisted that the cortege had to avoid the City and East End, which were hotbeds of working-class support. This was fiercely resisted by the organisers of the procession, and things came to a head at Cumberland Gate in Hyde Park. This was a symbolic location, close to the old ‘Tyburn Tree’ gallows and the earmarked site of the new Marble Arch, the monument to Waterloo. As tempers rose and brickbats were thrown, the Life Guards opened fire and killed two men, Richard Honey (a carpenter) and George Francis (a bricklayer). Like a self-fulfilling prophecy, the British state had once again shown its true colours.

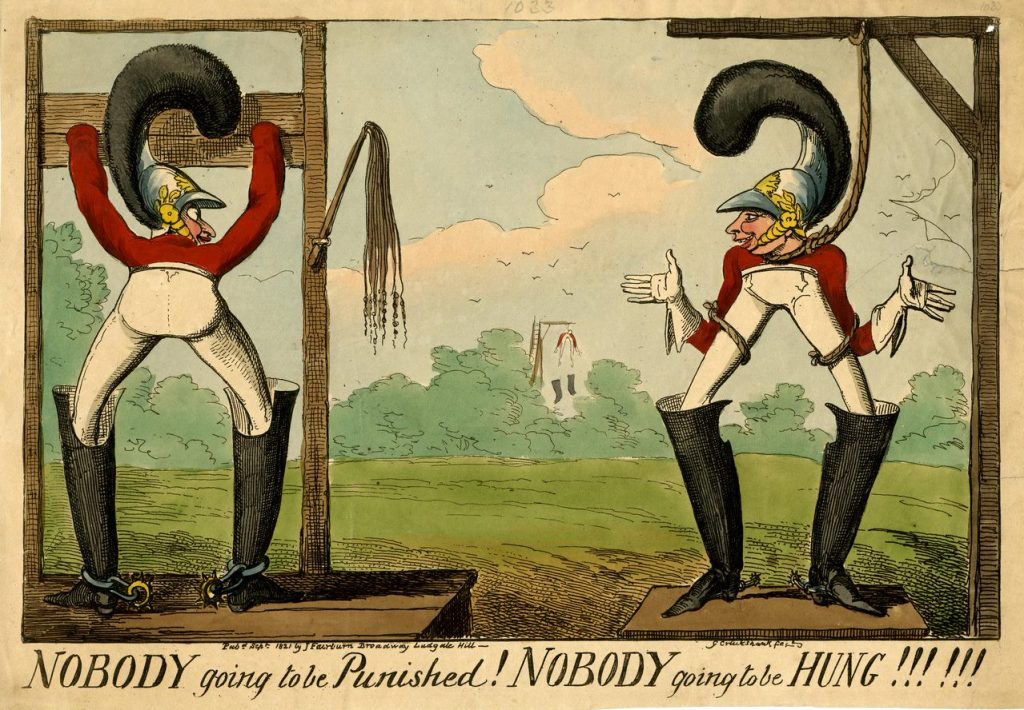

Through its ineptitude or sheer malice, the British state had handed a propaganda gift to Caroline’s side, and the caricaturists were quick to respond. Robert Cruikshank’s depiction of the event (Figure 6) was clearly based on his brother George’s well-known portrayals of Peterloo, Manchester Heroes and Britons Strike Home![15]The mounted soldiers mowing down protestors and the supplicating female figure in the foreground are hallmarks of the earlier prints, to which The Funeral Procession of Queen Caroline adds evidence of crowd aggression, perhaps in an attempt to be even-handed. George Cruikshank had no such qualms about apportioning blame and demanding retribution. His striking unpublished design, Vox Populi, Vox Dei (Figure 1), shows a military officer subjected to a traditional form of popular punishment known as the skimmington or charivari. This type of public humiliation of an offender was on the wane in the nineteenth century, but there are several putative reasons why Cruikshank deemed it an appropriate visual statement of justice. The most obvious justification was to redress the failure of the judicial process. Just as with Peterloo, no one was prosecuted for the shootings, even though many witnesses at the inquest into the deaths of Honey and Francis testified that an officer called (astonishingly) Gore had ordered the fatal shots.[16] This is almost certainly the pitiable figure riding backwards on the ass, his broken sword symbolizing his fall from grace. He has been found guilty in the court of public opinion: ‘Vox Populi, Vox Dei’. To avoid stereotypical associations with mob violence and Jacobin terror, the base of this sculptural composition combines two reassuring republican symbols: the fasces of ancient Roman magistrates (though without the axes), and the crossed hands of amity and solidarity. Echoing press reports of banners and placards at the event, the people are ‘Firm, ‘United’ and ‘Triumphant’, secure in their moral and political righteousness. This is clearly wish-fulfilment, and to modern eyes any celebration of vigilantism makes uncomfortable viewing. But the image is sombre rather than triumphal, and its ultimate purpose is to expose and exhibit wrongdoing. In this sense, the charivari or ‘rough justice’ is a metaphor for caricature itself, an affinity which Punch magazine took to heart in its subtitle ‘The London Charivari’.

We can only speculate about the effect Cruikshank’s unpublished print may have had. For all its restraint, the starkness of the tribute to popular justice may have been regarded as inflammatory, and this might explain why it was not published. By contrast, the prints that Cruikshank did publish in response to the funeral shootings showcase his visual wit and theatrical brio. The Man-Slaughter-Men and Nobody going to be Punished! (Figures 7-8) ridicule the idea that ‘nobody’ committed the crime by literally showing absurdly elongated soldiers without a body. In The Man-Slaughter-Men three gun-toting soldiers (though not the fourth, who looks horrified) jeer at the ghosts of Joyce and Francis who have arisen from their graves, their headstones inscribed with the actual findings of the inquests, manslaughter and willful murder. The scene derives its initial power from the inverted dramatic situation, as conventionally it is the ghosts who point their fingers at the guilty. Moreover, the perpetrators are also verbally dominant: while the ghosts are silent (no ‘vox populi’ here), the soldiers spout modified lines from Macbeth (3.4.49-50). When Macbeth sees the ghost of the murdered Banquo, he retorts, ‘Thou canst not say I did it; never shake/ Thy gory locks at me’. In the print the word ‘gory’ has been changed to ‘bloody’ to avoid implicating the officer named in the inquest. But the last word (so to speak) is with the victims, as we all know the ultimate fate of Macbeth, and the empty gallows between the guilty and the innocent speak volumes.

Indeed, in Nobody going to be Punished! the gallows have become the location of the action. Unlike Vox Populi, Vox Dei, this is mock-punishment, a farcical show in which the two culprits, one in the stocks with his back to us, the other facing us with a loose-fitting rope round his neck, are engaged in jocular banter, as if this was a pleasant Sunday afternoon in the park. But their smugness is undercut precisely by the absence of bodies: the birch and the trapdoor are stationary, but all they need is a hand to activate them. There are also two clever visual surprises in the scene. In the distance is a second, very tall gallows from which a soldier is hanging and losing his ludicrously over-sized boots (as in bossy boots). It is unclear if this figure is meant to be real or an effigy, but either way this is a rather chilling vignette of popular retribution. Contrary to the print’s title, which could be the quoted words of the arrogant soldier, someone has already been hung; and, moreover, ‘ye cannot say who did it’, as there is nobody about. Finally, the two grotesquely over-sized plumes of the soldiers resemble speech marks or parentheses, the vacated space of the unstated guilty verdict, the last words of the vox populi.[17]

The proliferation of controversial and entertaining images generated by Caroline’s death is testimony to the unprecedented role that caricature played in her campaign to become a legitimate queen. The satirical prints aided, abetted (and to lesser extent obstructed) her cause in extraordinarily creative and resourceful ways, mobilizing both high and popular culture and giving her multiple identities, contexts, and agencies. Caroline prided herself on being the people’s queen, and it was in the world of caricature that her image was truly nationalized. For the caricaturist, everybody is a body for everyone, and nobody can evade the satirical gaze. In an era when public image was becoming an increasingly important factor in social and political success, it was caricature that constantly called the visual bluff of celebrity and power.

Indeed, was the whole elite system of pomp and ceremony, in Robert Cruikshank’s term, simply All My Eye – in other words, nonsense?[18] All My Eye was Robert’s reply to his brother’s earlier celebration of Caroline’s democratic credentials (see the ‘November 1820’ blog), and as so often in caricature, the phrase draws attention to the act of looking (Figures 9-10). So I leave you to look at these two caricatures, and you can decide which print takes the crown.

[1] See Gynecocracy: With an Essay on Fornication, Adultery, and Incest (J. J. Stockdale, 1821), 655. The title refers to rule by women.

[2] This was of course a politically motivated smear: see Caillan Davenport and Shushma Malik, ‘The faces of Messalina,’ The Museum: The Magazine of the National Museum of Australia, 14: 10-15. In Georgian caricature, allusions to Messalina were often used to tarnish the reputations of political women: see, for example, Gillray’s The Offering to Liberty (1789; British Museum Satires 7548) which attacks Marie-Antoinette, and Dido in Despair (1801; British Museum Satires 9752) which targets Emma Hamilton.

[3] Messalina (T. Wright, 1821), 204. Wright was one of the main publishers of loyalist propaganda.

[4] See for example, A certain Dutchess kissing old swelter-in-grease the butcher for his vote (1874; British Museum Satires 6533). For a discussion of this campaign, see Neil Howe, Statesmen in Caricature: The Great Rivalry of Fox and Pitt the Younger in the Age of the Political Cartoon (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), Chapter 3.

[5] A Letter to the Queen by a Widowed Wife Sixth Edition (W. Wright, 1820), 12.

[6] Humphrey was probably assisted by Theodore Lane. The best collection of these prints is a shop album in the possession of the Lewis Walpole Library: see https://walpole.library.yale.edu/news/humphrey-shop-album-conserved-and-cataloged.

[7] Caroline commissioned the Italian artist Carloni (sic) to paint The Public Entry of the Queen into Jerusalem when she returned from her tour of the Middle East. The painting was exhibited in London in 1820, accompanied by a 16-page pamphlet which provided a key to the principal characters. The vainglorious echoes of Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (a scene painted by Keats’s friend Benjamin Robert Haydon, and also on show in 1820) were not lost on anti-Caroline satirists, and the painting was parodied on the cover of the illustrated satirical pamphlet The New Pilgrim’s Progress: Or, A Journey to Jerusalem (W. Wright, 1820). To add another layer to this rich intertextual playfulness, the latter image alludes to the many illustrations of Bunyan’s famous story, but echoes the design of William Blake’s and Thomas Stothard’s depictions of The Canterbury Tales. I am grateful to David Fallon and Elayne Gardstein for reminding me of these parallels.’Décolletée over-dress’ is M Dorothy George’s phrase in her description of the print in the British Museum Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires, now included in the online Collection: see the commentary accompanying British Museum Satires 14188.

[8] Rosemary Ellen Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft, and Wicca (Hermitage, 2008), 217.

[9] According to one of the typical pamphlets that was rushed into print, Louges was ‘inconsolable’ at Caroline’s death (Death of Her Majesty (Thomas Dolby, 1821), 9).

[10] According to the Examiner (22 July 1821), ‘hisses and plaudits…about equalled each other in strength’ at the coronation ceremony, and ‘Not the slightest popular feeling was called forth’ by the illuminations in the evening.

[11] ‘Verses on the Death of Her Majesty Queen Caroline’ (Pitts, Wholesale Toy Warehouse, 7 Dials). The poem is contained in a scrapbook, Satirical Songs and Miscellaneous Papers Connected with the Trial of Queen Caroline, held in the British Library.

[12] For attacks on George’s Irish visit, see Charles Williams’s caricature An Irish Wake (British Museum Satires 14241), and the verse satire Last Moments of Caroline (J. Johnston [1821]). In the latter, Caroline’s ghost appears to George and warns him that unless he mends his ways, there will be no ‘royal passport’ to heaven (14).

[13] Times, 15 August 1821.

[14] Caroline’s coffin was a controversial and contested symbol to the very end. During the night of 15 August, while the funeral cortege rested overnight in Colchester, government representatives entered St Peter’s church where her body lay and replaced the coffin’s inscription ‘Injured Queen’ with a loyal reference to the ‘potent’ king. According to the Times (17 August), the ‘royal victim’ was treated with a ‘remorseless indecency and indignity’ which echoed Peterloo (the ‘Manchester day’) two years earlier. The incident is still remembered locally: http://www.stpeterscol.org.uk/rumpus.html.

[15] British Museum Satires 14242. For the earlier prints, see British Museum Satires 13258 and 13266.

[16] Times, 18 August 1821; Examiner, 26 August 1821.

[17] In reality, the violent repercussions of Caroline’s death continued to spread. History almost repeated itself when the funeral of Honey and Francis on 26 August flared into violence outside Kensington barracks. The ceremony, one of the first examples of a working-class political funeral, deliberately retraced the route of the great processions to Hammersmith which were such a feature of the previous year. An estimated 70-80,000 people flocked to Hammersmith church where Caroline worshipped (her pew was still draped in black). On the return journey, insults and then blows were traded between protestors and drunken troops. High Sheriff Robert Waithman narrowly missed being shot dead by a Life Guard, and a second ‘Caroline Peterloo’ was averted by a whisker. See Joseph Nightingale, Memoirs of the Public and Private Life of Queen Caroline 3 vols (1820-22), 3: 380-9; Times, 29 August 1821; Examiner 2 September 1821. The graves of Honey and Joyce can still be seen in Hammersmith Church: see https://flickeringlamps.com/2014/07/09/fallen-comrades-caroline-of-brunswicks-life-and-death-in-hammersmith/

[18] Eric Partridge, Routledge Dictionary of Historical Slang, Sixth Edition (Taylor and Francis, 2006), 54.