by Miriam Al Jamil

Miriam Al Jamil is an independent researcher, with interests in eighteenth-century sculpture, material culture, and women’s history. She has published reviews and essays on online platforms and in academic journals including the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, Studies in Religion and Enlightenment, and Early Modern Women. Her chapter on a Zoffany painting appeared in Antiquity and Enlightenment Culture: New Approaches and Perspectives (Brill, 2020). She is the Fine Arts review editor for BSECS Criticks, chair of the Burney Society UK, and is active in the Johnson Society and Women’s Studies Group, 1558-1837.

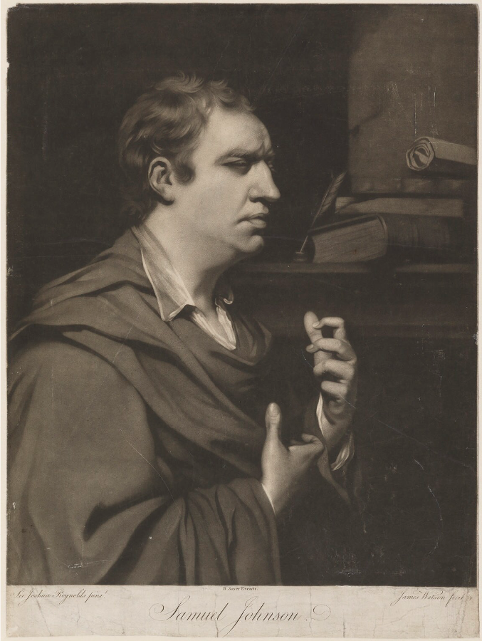

One of the best-known portraits of Samuel Johnson by Joshua Reynolds entered the collection of the 3rd Duke of Dorset at Knole in Kent after its exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1770. Often styled ‘Johnson Arguing’, the portrait rapidly deteriorated, ‘the face cracked, the shadows damaged by bitumen’, due to Reynolds’ experiments with untested media. (1) As a result, the details of the painting are better appreciated from the 1769 mezzotint (figure 1) by James Watson (1740-1790). (2) Mark Hallett notes that ‘Johnson’s portrait offers an especially startling depiction of heightened, active introspection, conveyed most powerfully by his half-closed eyes and by the hands that claw the air as if grappling with, or playing on, an especially complex set of concepts.’ (3) The hands add tension to the portrait, capturing a moment when the whole body engages with a critical point in his thought process. However, the combination of an idealised, classicised Johnsonian face with strangely distorted and twisted hands has troubled commentators ever since it was first shown, the ‘hands raised and bent in a peculiar manner’. (4) Watson’s print is unusual among the variety of subsequent engraved copies featuring the face alone which form the subject of this essay.

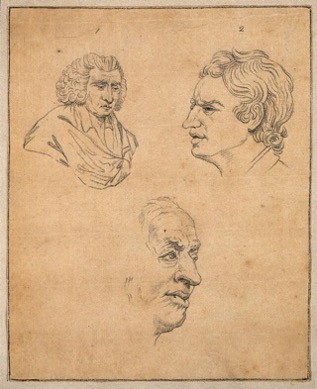

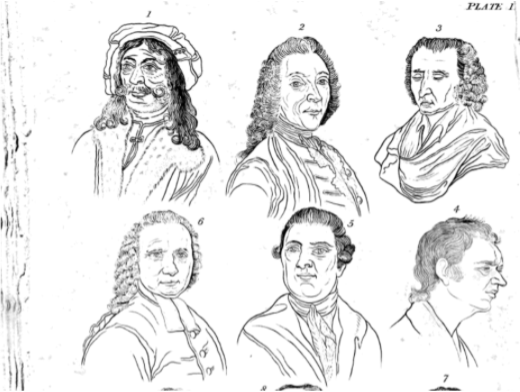

The vocabulary of gesture and representation of the passions through facial expression was the subject of illustrated treatises which proliferated from the seventeenth century to inform and guide both artists and actors, lawyers and preachers, all of whom depended on public performance to some extent in their professions. (5) At a popular level, George Alexander Stevens published his ‘A Lecture on Heads’ in 1765, based on his demonstrations which used a range of busts as props to illustrate and satirise popular character stereotypes (see figure 2).

Frontispiece, from “A Lecture on Heads” by George Alexander Stevens, 1808, print. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Stevens describes ‘The Learned Critic, or Word-grabber’: ‘This is a true classical conjugating countenance, and denotes dictionary dignity […] the ears of this critic are immensely large; they are called trap doors to catch syllables![…] his eyes are half closed; that’s called the Wiseman’s Wink; and shews (sic) he can see the world with half an eye.’ (6) Most interpretations of the half-closed eyes in Johnson’s portraits tend to point either to his disability directly or to his introspection rather than to shrewd engagement with the world. Stevens’ idea poses the possibility of an alternative and artful evaluation of Johnson’s half-closed eyes in the Knole portrait. Johnson might have enjoyed the epithet ‘Wiseman’s wink’.

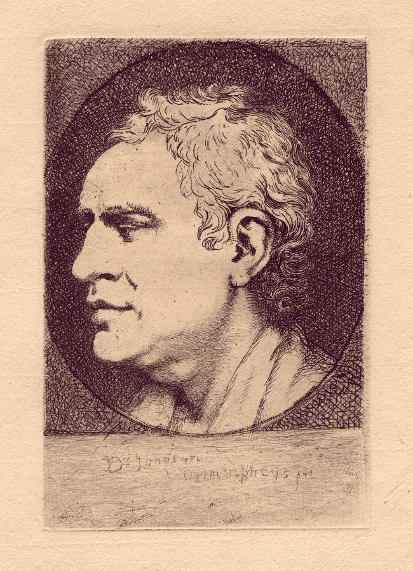

The most influential contemporary analysis of gesture and appearance was one cited by James Boswell who listed all the known portraits of Johnson in a footnote to his Life of Johnson (1791). (7) These include one published in John Caspar Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy (1789-98), ‘in which Johnson’s countenance is analysed upon the principles of that fanciful writer’. (8) The Knole portrait provided the most fruitful source for Lavater’s examination of Johnson’s character based on facial expression and physical peculiarities. The engraver Thomas Holloway (1748-1827) furnished many of the 800 illustrations to Henry Hunter’s translation of Lavater of 1789. His three Johnson portraits are pared down and simplified in line, combined on the page to enable subtle interaction in an exploration of the portrait subject (figure 3).

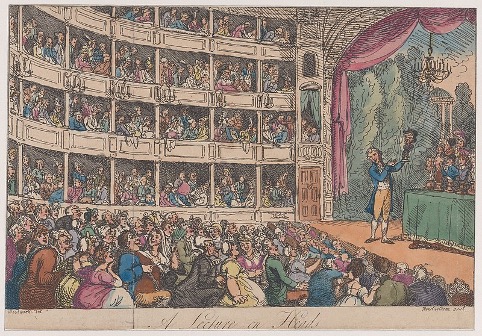

Thomas Holcroft’s translated edition of Lavater’s essays uses another engraving of the Knole portrait which has been divested of its introspective ‘wrestling’ altogether (figure 4). The description adds a further interpretation of Johnson’s expression, ‘the most unpractised eye will easily discover, […] the acute, the comprehensive, the capacious mind, not easily deceived, and rather inclined to suspicion than credulity’. (9) An appended essay in this edition by essayist Helfrich Peter Sturz (1736-1779) asserts that ‘Dr. Johnson had the appearance of a Porter; not the glance of the eye, not any trait of the mouth, speak the man of penetration, or of Science.’ (10) He continues, ‘Can a countenance more tranquilly fine be imagined, one that more possesses the sensibility of understanding, planning, scrutinizing? In the eyebrows, only, and their horizontal position, how great is the expression of profound, exquisite, penetrating understanding!’. (11) For Sturz, the character is belied by his attire. His assessment incorporates his familiarity with anecdotes about Johnson’s habitually dishevelled dress although the print itself does not include any evidence to support his analogy. An imagined substitution for the classical robe of Reynolds’ original painting enables the print to become a convenient signifier of Johnson, the man remembered by his friends.

Figure 4. From Lavater, Essays in Physiognomy, translated from the German by Thomas Holcroft. London: Ward, Lock & Co., undated), 17th edition. Plate 1, Nos. 3 and 4, p.33.

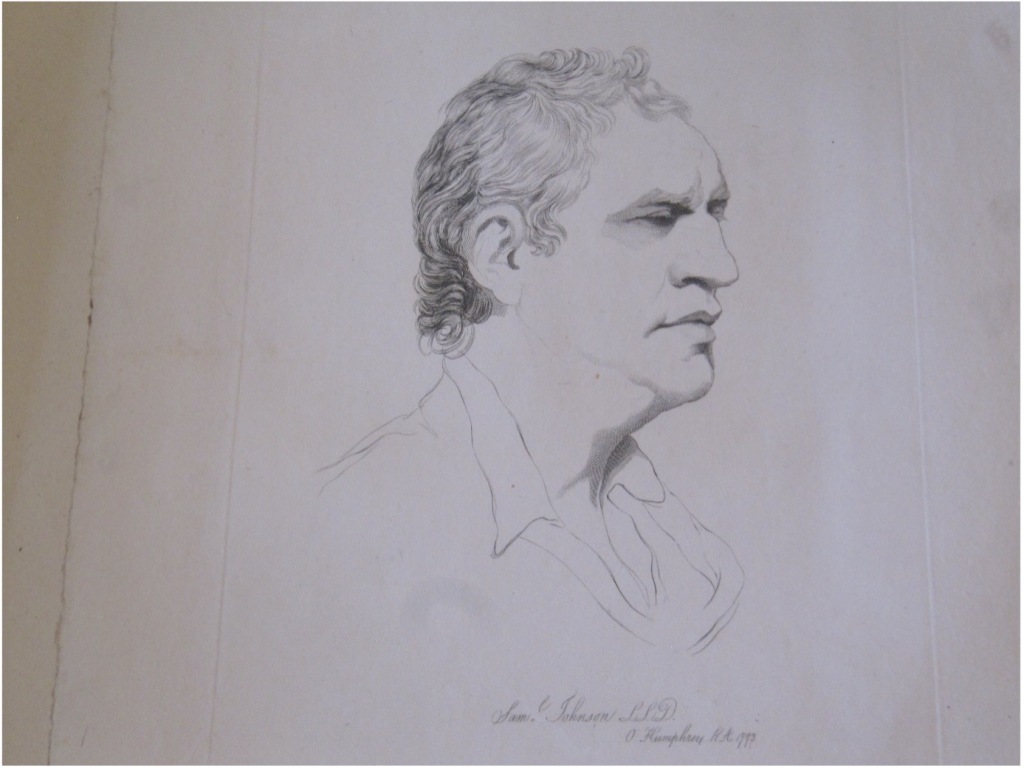

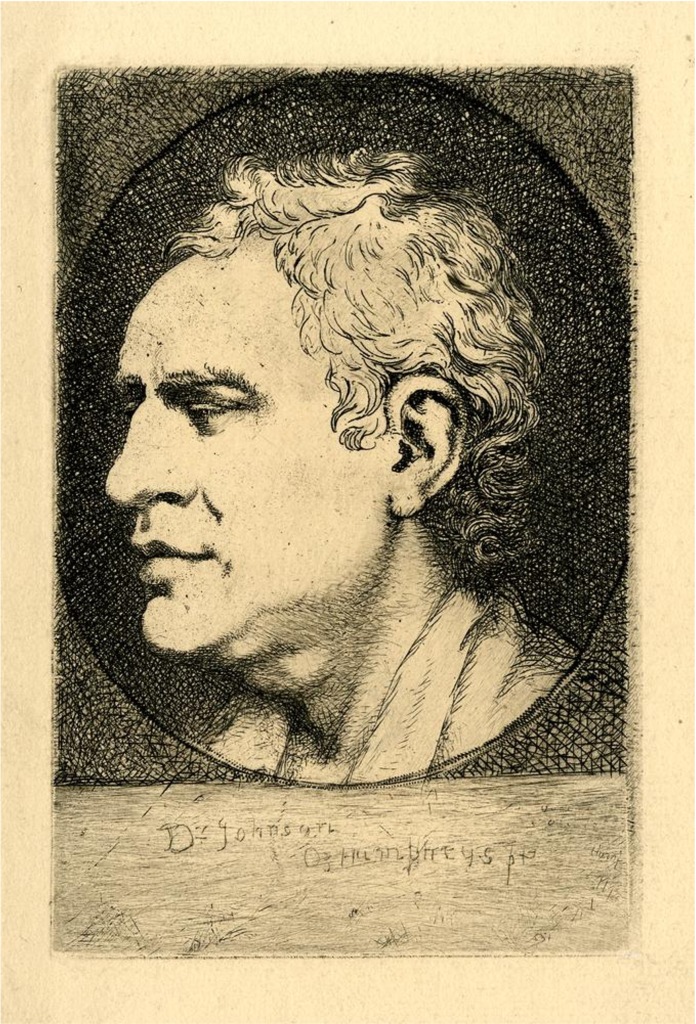

The portrait at Knole drew both visitors and copyists. One of these was Ozias Humphry (1742-1810), a skilled miniaturist who received the patronage of the 3rd Duke. He wrote about meeting Johnson sometime between 1764 and 1772: ‘I was very much struck with Mr. Johnson’s appearance, and could hardly help thinking him a madman for some time, as he sat waving over his breakfast like a lunatic. He is a very large man, and was dressed in a dirty brown coat and waistcoat with breeches that were brown also (though they had been crimson), and an old black wig.’ (12) Like Sturz, Humphry went on to describe how the peculiarities of the man had ill-prepared him for the brilliant intelligence that he then witnessed in action. He painted at least one portrait of Johnson. Boswell listed ‘a beautiful miniature in enamel’ but some of his later work has been lost. (13)

A 1918 biography of Humphry includes a copy of an etching of Johnson’s head taken from the Knole portrait, reputedly based on a drawing by Humphry. The etching is described, ‘From the rare etching after Humphry by Mrs. D. Turner, Original Unknown’. (14) Before 22nd July 2021, the National Portrait Gallery website attributed the print to Mrs. D. Turner, based on this information. This attribution has now been removed, following my query, in favour of Samuel James Bouverie Haydon (1815-1891). (15) However, the NPG continues to list an etching by Mrs. D. Turner c.1825, based on a crayon copy by Humphry but it is not illustrated or part of the gallery’s collection. (16) She did indeed make an etching of Johnson, but it was not the one cited in Humphry’s biography or originally by the NPG.

Mary Dawson Turner was born Mary Palgrave in Norfolk, in 1774. She married the banker, botanist, antiquarian and collector Dawson Turner in 1796, with whom she lived in Great Yarmouth and had eleven children, eight of whom survived into adulthood. (17) Dawson Turner’s extensive collections have received scholarly attention over the years. In the Preface to his Manuscript Library sale of 1859, he is described as ‘an accomplished scholar, a man of very varied attainments, and of accurate observation […], deriving his solace and delight alike from pursuits connected with the fine arts and archaeology’. (18) He arranged tuition in drawing and engraving for Mary and their six daughters whose subsequent industry and dedication to the production of illustrations for his books and projects both amazed and unsettled visitors to their home. Their contributions to his work and reputation have only recently been acknowledged and examined in a collection of essays published in 2007. (19)

The collector’s family life appears close; he loved, respected and was proud of his wife and children. However, I suggest that the intensive application to their studies required of the children and the daily labour of etching from 6.30 in the morning undertaken by Mary and her daughters betokens something more obsessive in an ostensibly benign patriarchal home. Alluding to a visit to London by her daughter Ellen, Mary expressed concern over her rigorous studies, ‘I certainly think that her less comparatively sedentary habits and strenuous application of mind will probably be [more] friendly to her general health than those she addicted herself to at home’. In the same letter, Mary describes one of her own etching subjects as ‘drudgery’ from which she needed ‘some precious rest to the eyes and pleasure to the mind’. (20) This feverish labour is the context in which Mary etched her print of Dr. Johnson.

Dawson Turner’s ‘grangerised’ volumes of James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson (1791) are all now lost. These consisted of two sets of four volumes which were each made into six large imperial folio volumes, with around 1,700 portrait prints, views of locations mentioned in the text, news cuttings and autographs. It is likely that Mary’s etching of Johnson was destined for one of these volumes. Mary mentions her efforts to complete it in a letter of 1825. The cares of her household and large family and her own fragile health clearly interfered with the relentless etching programme which demanded her attention. She writes, ‘I have been so variously engaged today with perpetual calls for directions to whitewashers, whitesmith masons & etc. that I have not done Dr, Johnson’s head’. (21) An unpublished volume, of which only forty-nine copies were made, One Hundred Etchings by Mrs. Dawson Turner, includes Mary’s etching, ‘Johnson, Samuel LL.D, from a drawing by Ozias Humphry R.A. 1773’. (22) It is a disciplined and technically exact copy which was reproduced in other Dawson Turner print albums.

The Mother’s Exemplar, being a collection of Etchings, many of them from Original Drawings by Mrs. Dawson Turner and her family

V&A Prints and Drawings, 93 H/19.

In her study of eighteenth and nineteenth century-extra-illustrated books, Lucy Peltz identifies many cases where fathers and daughters undertook such an activity together. In the Turner family, she suggests, it was ‘a domestication of the intellectual sociability of the masculine club’ which gave the daughters ‘access to a traditionally male arena’ and ‘strengthened sentimental bonds between relatives’. (23) Such a bond is evident particularly in correspondence from Harriet Turner to her father which centres on the art she has seen and the subjects she has produced as drawings and etchings. Her enthusiasm is undeniable, but she is passionate and needy, longing for his approval and affection, even after she has married and moved away. (24) The illustrations chosen for inclusion in Turner’s volumes depended largely on the creative production of the Turner women over many years, a more demanding commitment than the leisurely and companionable selection of relevant prints from other sources which is suggested by Peltz’s statement.

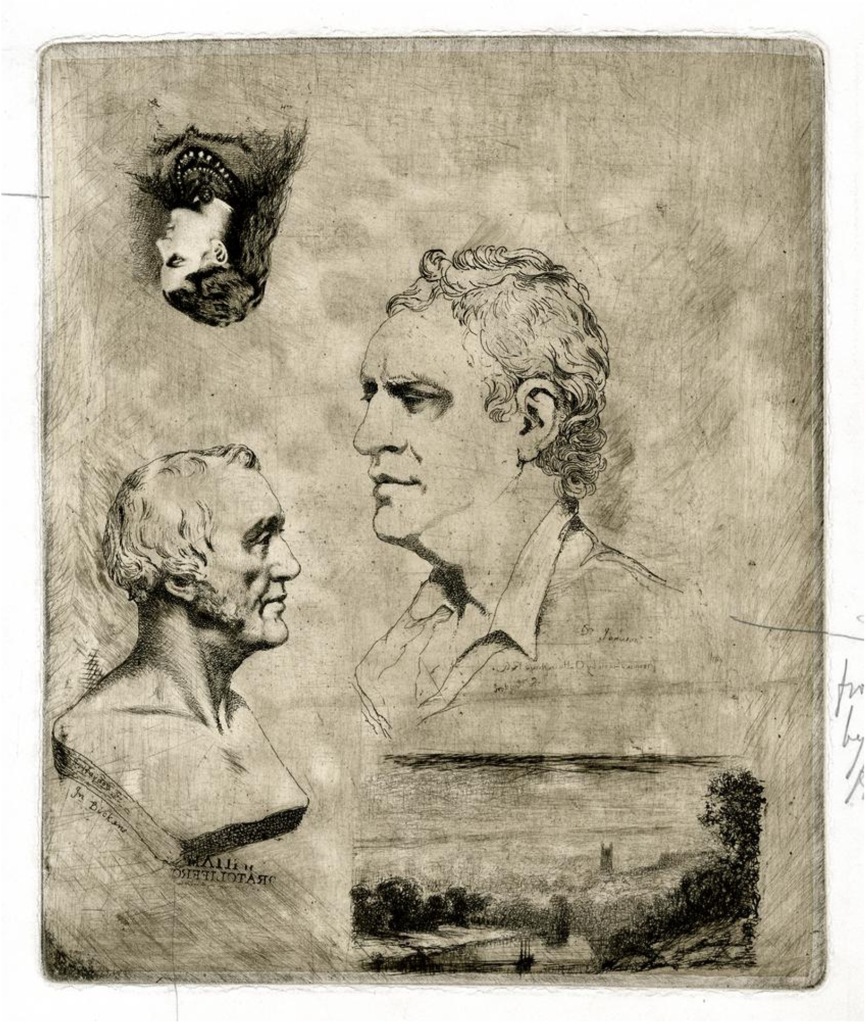

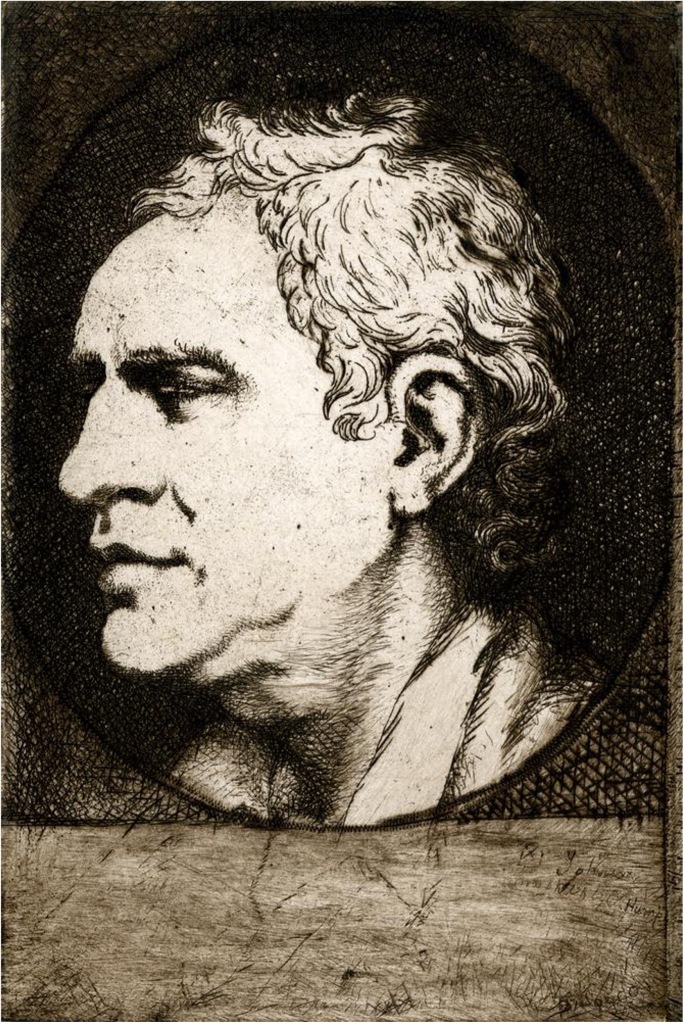

The inaccessibility of both Mary Turner’s print and of the lost Humphry drawing upon which it was based led to confusion over the attribution for another print, ostensibly after the same Humphry drawing. Samuel James Bouverie Haydon (1815-1891), print-maker and sculptor, made his etching of Johnson in 1860. Unlike Mary Turner, he did not alter the reverse image. The process of making his print is evident in plates held by the British Museum. He etched an early version on a large 32cm high plate, alongside trial etchings of a bust of John Dickens, a portrait of his daughter and a small landscape (figure 6). (25 ) He then trimmed the portrait down and added an oval frame which was probably close to the format of the original Humphry miniature portrait (figure 7). (26) He later burnished out and replaced the lettering on the earlier plate (figure 8). (27)

Figure 6. Samuel James Bouverie Haydon, etching on copper, c.1860, 320 x 265mm. British Museum, No. 1924,0512.18

Figure 7. Haydon, Portrait Head of Dr. Johnson, c.1860., 174 x 115mm. British Museum, No. 1832,0507.30.

Another print of this final version is the one in the NPG collection (figure 9). (28) A comparison with Mary Turner’s print highlights Haydon’s dense and less formal cross-hatching of the background to deepen the contrast to the face, and his spare treatment of the hair with less expressive line and a consequent lack of movement and flow.

The reason that Haydon undertook the etching is not known. He worked at his home in Exeter and in London. (29) He regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1840 until 1876 and combined his traditional artistic practice with the pioneering medium of photography from 1845, when he worked as an assistant to William Fox Talbot. His academy exhibits reflect commissions for civic, ecclesiastical, military and aristocratic portrait busts, classical and sentimental subjects, and paintings of town and country locations. (30) The variety of his subjects point to an artist who adapted to the economic imperatives of the market, and though not universally celebrated, at least he made a living through his craft. The four trial etchings together on his plate summarise the diversity of the media he employed. In this context, Johnson’s head becomes inextricably linked with the cultural and commercial conditions of nineteenth-century London.

Unlike Haydon, Mary Turner and her daughters worked solely on Dawson Turner’s projects, never exhibited their art at public exhibitions and do not appear to have aspired to general artistic recognition. However, Jane Knowles in her essay on the Turner family identifies a hint of regret in one of Elizabeth Turner’s letters, ‘We can copy & that is all. And Mr. Varley’s kind efforts & example have only show’d to prove to us the strong line of demarcation which separates the artist from the draftsman’. (31) Knowles suggests that Dawson Turner regarded them as copyists, as merely ‘artistic’ rather than ‘artists’, who were never expected to develop an individual style. Maurice H. Grant, in his A Dictionary of British Etchers (1952) is dismissive about Mary, ‘all competent little Plates without much finesse but firmly etched somewhat in the Netherlands tradition’. (32) Likewise, his entries for the Turner daughters are perfunctory, ‘They chiefly employed themselves in copying the sketches of J.S. Cotman, their instructor, but their several works are not now distinguishable’. (33) A recent dictionary of print-makers does not include etchers so fails to mention the Turners at all. (34) It is not surprising that Mary Turner’s etching of Johnson has been forced back into obscurity and inaccessibility and her name incorrectly attached to another artist’s work. Technical skill and a trained eye are no substitute for creative response.

Footnotes

(1) David Mannings, Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings (New Haven: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University Press, 2000), no. 1012, p.280.

(2) See Mark Hallett, Reynolds: Portraiture in Action (New Haven: The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, Yale University Press, 2014), p.242; James Watson, Samuel Johnson, 10 July 1769, National Portrait Gallery, NPG D36536; see entry for James Watson in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-28840?rskey=u5GJ4E&result=4 [accessed 18 November, 2021].

(3) Hallett, p.244.

(4) Edward Hamilton, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Engraved Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, P.R.A, from 1755 to 1820 (London: Colnaghi & Co., 1874), p.32.

(5) For a full discussion of available treatises, see Adam Kendon, Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), Chapter 3.

(6) George Alexander Stevens, The Celebrated Lecture on Heads, which has been exhibited upwards of One Hundred Successive Nights, To Crouded Audiences, and Met with the most Universal Applause (London: Richard Bond, 1765), Part III, p.15.

(7) James Boswell, Life of Johnson unabridged (Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), Monday 20 December, 1784, p.1395, footnote 1.

(8) Johann Caspar Lavater, Essays on physiognomy; designed to promote the knowledge and the love of mankind, Illustrated by more than eight hundred engravings accurately copied; and some duplicates added from originals. Executed by, or under the inspection of Thomas Holloway. Translated from the French by Henry Hunter (London: John Murray [etc.], 1789-98), 5 Vols.; https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yffvbzu5 [accessed 18 November, 2021].

(9) Essays on Physiognomy: translated from the German of John Caspar Lavater, by Thomas Holcroft. Also One Hundred Physiognomical Rules, taken from a posthumous work by J.C. Lavater; and a Memoir of the Author, seventeenth edition; Illustrated with upwards of four hundred profiles (London: Ward, Lock & Co., undated), p.33.

(10) Ibid., p.257.

(11) Ibid., p.258.

(12) Quoted from letter, private collection, in George C. Williamson, Life and Works of Ozias Humphry, RA (London: John Lane, 1918), p.87.

(13) Boswell, p.1395, footnote 1.

(14) Williamson, List of Illustrations, p.xiv, and facing p.88.

(15) National Portrait Gallery, NPG D3158.

(16) See National Portrait Gallery, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw03492/Samuel-Johnson#ref4 [accessed 12 October, 2021].

(17) Mary Dawson Turner (1774-1850), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Dawson_Turner [accessed 12 October, 2021]; see the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Turner, Dawson (1775-1858), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-27846 [accessed 12 October, 2021].

(18) Catalogue of the Important Manuscript Library of the late Dawson Turner, esq., formerly of Yarmouth […] to be sold by auction on Monday, June 6th, and following days’, Messrs. Puttick & Simpson, Auctioneers of Literary Property, 47 Leicester Sq., 1859, p.xvi.

(19) Nigel Goodman, ed., Dawson Turner: A Norfolk Antiquary and his Remarkable Family (Chichester: Phillimore, 2007).

(20) Trinity College Library, Cambridge, Dawson Turner Correspondence, Turner III, A33/42, Mary Turner to Dawson Turner, 5 April 1832.

(21) Dawson Turner Correspondence, Turner III, letter from Mary Turner, 19 April 1825.

(22) Turner, One Hundred Etchings by Mrs. Dawson Turner, Not published, [1830], British Library; other copies discussed by Warren R. Dawson, ‘A Bibliography of the Printed Works of Dawson Turner’, in Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society, (3:3, 1961), pp.232-256, 242.

(23) Lucy Peltz, Facing the Text: Extra-illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769-1840 (San Marino: The Huntington Library, 2017), p.313.

(24) See especially Dawson Turner Correspondence, Turner III, A8/1-35 Harriet Turner (Gunn) to Dawson Turner.

(25) Samuel James Bouverie Haydon, etching on copper, c.1860, 320 x 265mm, British Museum, No. 1924,0512.18 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1924-0512-18 [accessed 29 October, 2021].

(26) Haydon, Portrait Head of Dr. Johnson, c.1860, 174 x 115mm, British Museum, No. 1832,0507.30 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1932-0507-30 [accessed 29 October, 2021].

(27) Haydon, Portrait of Samuel Johnson, c.1860, 176 x 116mm, British Museum, No. 1913,0611.122 https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1913-0611-122 [accessed 29 October, 2021].

(28) Haydon, Samuel Johnson, National Portrait Gallery, 283 x 203mm, PG D3158. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw37354/Samuel-Johnson?LinkID=mp02446&wPage=1&role=sit&rNo=39 [accessed 29 October, 2021]. My thanks to British Museum curator Hugo Chapman and National Portrait Gallery curator Paul Cox.

(29) For biographical details, see Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland, 1851-1951:https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib7_1218129055 [accessed 7 November, 2021].

(30) See entries in The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769-2018: https://chronicle250.com/1840#catalogue [accessed 7 November, 2021].

(31) Elizabeth Turner, quoted in Jane Knowles, ‘A Tasteful Occupation? The Work of Maria, Elizabeth, Mary Anne, Harriet, Hannah, Sarah and Ellen Turner’, in Nigel Goodman, Dawson Turner, pp.123-140, p.136; reference is to John Varley, artist (1778-1842), acquaintance of the family.

(32) Col. Maurice Harold Grant, A Dictionary of British Etchers (London: Rockliff, 1952), p.207.

(33) Ibid., p. 208.

(34) See David Alexander, A Biographical Dictionary of British and Irish Engravers, 1714-1820 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021). Crome, Cotman and Varley, all associated with Dawson Turner, are included.