by Jessica Ghyvoronsky

Jessica Ghyvoronsky is an artist, collector, and artist advocate based in Seattle, WA. She received both of her Bachelors degrees from the University of Washington in Interdisciplinary Visual Arts as well as Philosophy, and received her MFA in Visual Art from Azusa Pacific University. She has been active in the Seattle art world through her ventures Seattle Art Post and River Seattle, and has recently begun apprenticing in the realm of appraising fine art and antiques, working towards her Appraiser Certification through the Appraiser’s Association of America. She feels very lucky to own 18 of the original engravings, as they are rare and important artifacts that document the intersection of literature and visual arts of the 18th century in such a specific way. Her nearest goal is to collect the rest of the Seven Ages of Man – Stages 1-3, to complete that portion of the collection. Most of the prints are for sale on Etsy.

It was June 2024 when I was helping organize the attic of an antique shop I work with, sorting through a room full of boxes and antique items, when we came across a stack of large prints that were loosely draped behind a large pile of boxes. The sixteen prints were each in their own individual protective sleeve, and the stack was almost tri-folded. The prints were thankfully not creased, but certainly left in a state where we knew they’d require some love and effort to flatten them out again. They had been there for years, and were just seeing light again. I have always been drawn to antique etchings and engravings, but these were notably more beautiful than most of the works I’ve seen before, in the Romantic age style, all featuring scenes from some of Shakespeare’s most iconic plays. I was smitten, to say the least, and ended up procuring them and begun the process of carefully flattening the pages at home while researching the collection. I reached out to Shakespeare and Boydell experts all around the world, and owe most of my thanks to Dr. Rosemary Dias, who confirmed that I did indeed have the original large-format engravings that were first released by the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery and pointed me toward great references to learn more.

Laying out the prints all together for the first time.

Not a month into my research, my husband Mikhail and I were driving in Mount Vernon Washington and happened upon an Antique Fair that was ending that very day. Of course we had to stop by, and to my surprise while perusing a vendor’s inventory, I found two Boydell Shakespeare prints for sale, of the same large size format. The chances of this happening were extremely rare, one might even venture to name Fate as responsible. Since many of these engravings were originally bound into a folio and eventually became separated as individual works of art, most of these prints have been trimmed down in size from their original state to fit into frames more evenly. This is the case for these two prints I stumbled upon at the Antique Fair. The rest of the 16 prints that I previously found in the attic of the antique shop, however, remain intact in their original size, untrimmed. These large folio-sized prints are rare and many are exhibited in such museums as The British Museum, The Met Museum, The Folger Shakespeare Library, and The Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago.

This brings me to the following study of all I have learned thus far about the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery and of these prized engravings from 1796 that came into my possession. Some of the original paintings from the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery have been destroyed or simply disappeared, leaving their engraved copies as the only evidence we have that they ever existed. All of the photos included in this article are my own, of the prints that I now have in my collection.

Finding two more prints at the antique fair.

The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery

In November 1786, Josiah Boydell, a printer and publisher, organized a dinner in London with prominent artists and important representatives of London. They came up with the idea of making a special edition of Shakespeare’s plays with illustrations. Just a week later, Josiah and his uncle John Boydell decided to go even bigger: they planned to open a place called The Shakespeare Gallery. This gallery opened in London’s Pall Mall in 1789. It displayed brand-new, life-size paintings of scenes and characters from Shakespeare’s plays. The gallery became very popular, charging one shilling for entry and attracting hundreds of visitors every day. This was around the time when museums like the British Museum were starting to become popular. Boydell saw this trend and used it to create a unique museum experience focused entirely on Shakespeare.

The Engravings

Boydell changed the art world by making it more commercial, moving away from relying solely on wealthy patrons. The Shakespeare Gallery was a prime example of this shift, demonstrating that art could be turned into prints and sold to many people. Large prints of the paintings in the gallery were sold through subscriptions starting in 1791. Smaller versions were included in a new edition of Shakespeare’s plays. It took ten years to publish the complete set of nine large folios in 1802. In 1803, Boydell printed two large books containing all of the engravings. Engraving became more popular in the 18th century, growing alongside the book industry as literacy grew. Boydell’s new way of marketing, combining exhibitions with print sales, became a model for others to follow, and inspired galleries like Thomas Macklin’s Poet Gallery, Henry Fuseli’s Milton Gallery, Blake’s Dante Gallery, and the Dore Gallery.

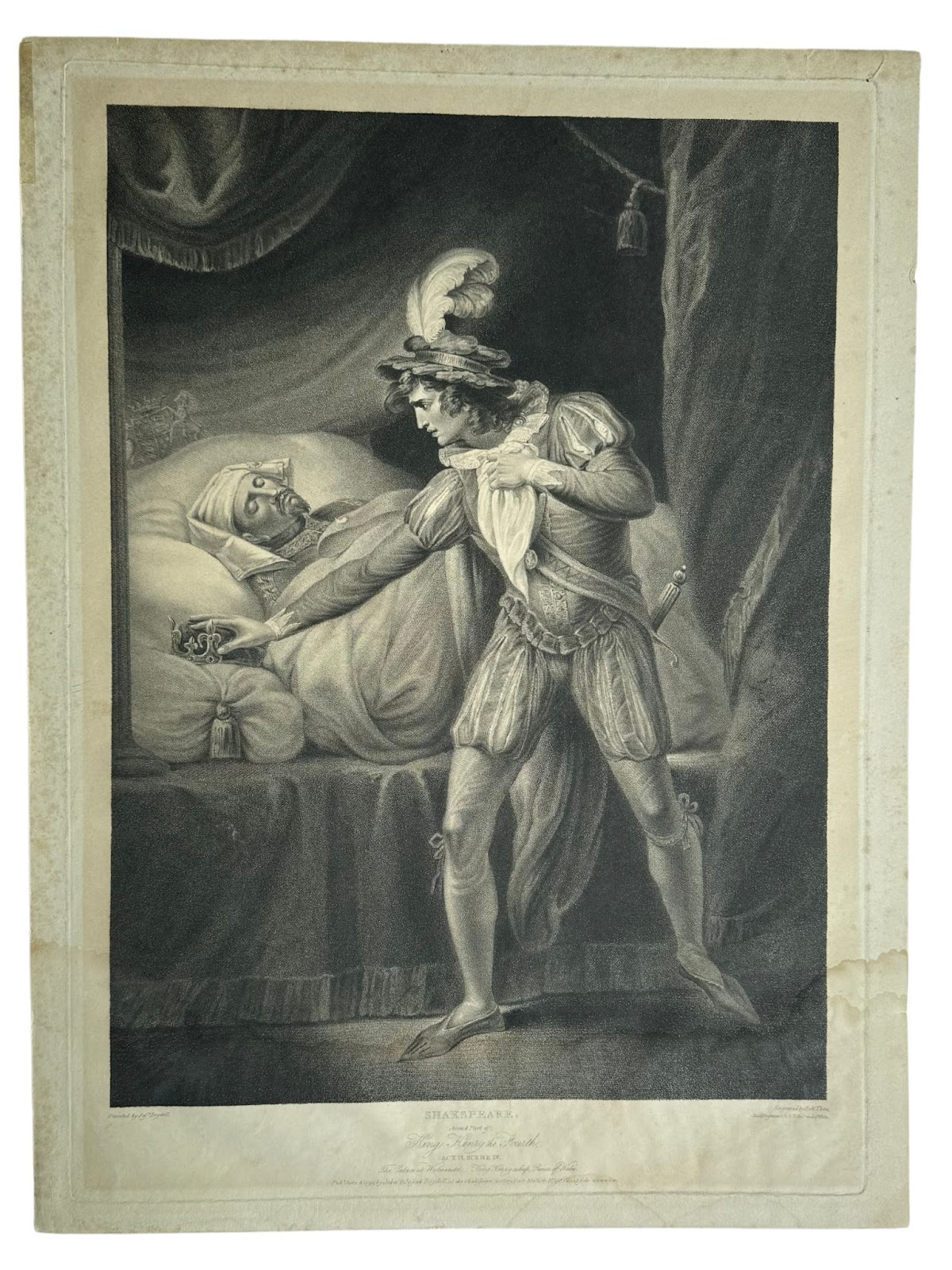

Josiah Boydell not only published the Shakespeare Gallery folios, he was also a painter. This picture shows a powerful moment from the play “King Henry IV, Part 2” where Prince Hal stands by his dying father’s bed and tries on the crown.

Josiah Boydell: Second Part of King Henry the Fourth. Act IV, scene iv. The Palace of Westminster. – King Henry asleep; Prince of Wales. Engraved by Robert Thew, published June 4, 1795.

History Painting

Boydell’s gallery brought a significant change to English painting. Previously, most artists earned their living by painting portraits for wealthy nobles. Boydell changed this by hiring top artists to create artworks based on Shakespeare, other writers, and English history. The Boydells aimed to promote British painting, focusing on History Painting. This type of art depicted important events and moral lessons, considered the most prestigious form of art at the time. Shakespeare, emerging as a national symbol, was an ideal subject for their endeavors. Boydell’s initiative created a demand for history paintings, providing artists with a new income source beyond portraits. Some artists worked on these projects for eight to ten years. Boydell paid generously for their works, offering painters around 500 pounds and engravers even more. This increased the popularity of history painting, placing it on par with portraits and landscape paintings.

Starting with 34 paintings in 1789, the collection grew to over 160 by 1802, profoundly shaping how Shakespeare was visually portrayed for generations. Boydell’s emphasis on history painting wasn’t accidental; it coincided with England’s recovery from a tumultuous period, including the Treaty of Versailles ending the American colonies’ war, which had divided Parliament and weakened the monarchy. As London’s Mayor, Boydell had a personal and political interest in promoting his country’s stability and the monarchy’s authority. He achieved this by glorifying England’s past through its greatest playwright. The Shakespeare Gallery not only celebrated England’s cultural and literary heritage but also revived national pride during a time of crisis. Visiting and supporting the Shakespeare Gallery became a way for people to show their patriotism. Boydell, though innovative for his time, faced bankruptcy due to his failure to meet the high standards of history painting and the loss of his European market during the French Revolution. The entire collection of 167 paintings was sold in a lottery and dispersed, with some artworks disappearing forever.

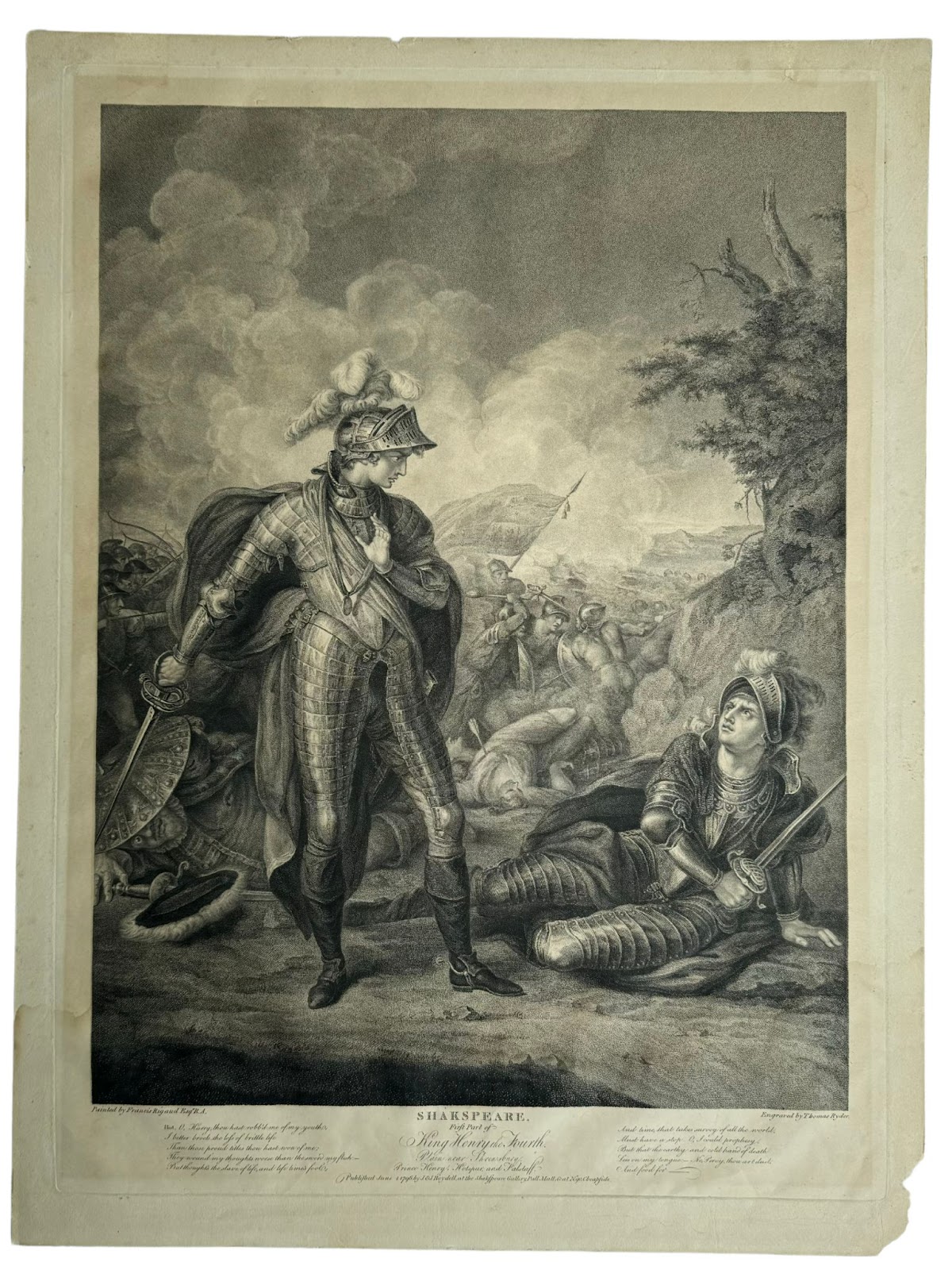

John Francis Rigaud: First Part of King Henry the Fourth. Act V, scene iv. Plain near Shrewsbury, Prince Henry, Hotspur, and Falstaff. Engraved by Thomas Ryder, published June 1, 1796.

Hot: O, Harry, thou hast robb’d me of my youth:

I better brook the loss of brittle life

Than those proud titles thou hast won of me;

They wound my thoughts worse than thy sword my flesh: –

But thought’s the slave of life, and life time’s fool;

And time, that takes survey of all the world,

Must have a stop. O, I could prophesy,

But that the earthy and cold hand of death

Lies on my tongue; – No, Percy, thou art dust,

And food for____”

In this battlefield scene, the artist shows a young soldier holding up a flag as a sign of victory, fearlessly leading his men into battle.

This piece shows a scene from William Shakespeare’s play where Prince Henry, Hotspur, and Falstaff are on a plain near Shrewsbury. In Shakespeare’s story, Prince Henry is determined to kill the rebellious knight Hotspur, who has fought against King Henry IV of England. The engraving depicts Hotspur being fatally wounded by Prince Henry during the battle of Shrewsbury, while Falstaff pretends to be injured or dead nearby.

Johann Heinrich Fuseli: The Tempest. Act I, Scene ii. The inchanted Island: Before the Cell of Prospero. – Prospero, Miranda, Caliban, & Ariel. Engraved by Jean Pierre Simon, published Sept 29, 1797. Location of original painting: City of York Art Gallery: Head of Prospero only.

“Pro. For this, be sure, tonight thou shalt have cramps,

Side-stiches that shall pen thy breath up; urchins

Shall, for that vast of night that they may work,

All exercise on thee: thou shalt be pinch’d

As thick as honey-combs, each pinch more stinging

Than bees that made them.”;

Various nationalist themes can be found in the way some of the artists chose to depict their scenes, as in The Tempest, where Prospero’s power is subtly undermined, questioning his right to sovereignty. At first pass, one might view Caliban as subservient victim and Prospero as the authoritative disciplinarian, but there are key details that undermine the supposed power of Prospero. The viewer’s eye is directed to Caliban, not Prospero. Caliban is just more interesting to look at – lit from above, where we practically see his full form and face (versus the half profile view of Prospero and Miranda), strong muscular body, striking and terrifying face. Seeing as how the artist Henri Fuseli spent a significant amount of his studies in Rome, viewing the works of Michelangelo, one can see the similarities to the Creation scene in the Sistine Chapel. Only here, Caliban’s form plays the role of God, with an outstretched defiant fist and Prospero the role of Adam, pointing accusatorily. It could be said that this is Fuseli’s commentary on the political climate in England, revealing King George as tyrannical and not the true Sovereign.

Rev Matthew Peters: King Henry the Eighth. Act V, scene iv. The Palace, Aldermen, Lord Mayor, Garter, Crammer, Duke of Norfolk & Marchioness of Dorset, God Mothers, & c. & c. Engraved by Joseph Collyer, published Dec 1, 1803.

“Cran. Let me speak, sir,

For Heaven now bids me; and the words I utter

Let none think flattery, for they’ll find them truth.

This royal infant (Heaven still move about her!)

Though in her cradle, yet now promises

Upon this land a thousand thousand blessings,

Which time shall bring to ripeness: she shall be

(But few now living can behold that goodness)

A pattern to all princes living with her,

And all that shall succeed;”

In this scene by Reverend Matthew Peters from King Henry the Eighth, Archbishop Cranmer’s influence over the King is feared, as the king trusts his integrity and rescues him from the hands of the conspiratorial nobles. To further demonstrate his endorsement of the Archbishop, the King has him serve as godfather at Elizabeth’s christening. The painting represents the union of Church and Monarchy, with the Church exhibiting more prominence and glory over the Monarchy.

The Stage

It is not surprising that many of the paintings in the Shakespeare Gallery feature scenes that look like they could’ve been captured on the theater stage. It would have been impossible for the artists to have not been influenced by their visual experiences as theatergoers while recreating their scenes into painting.

In this scene, Robert Smirke portrays a play-within-a-play by Shakespeare, framed by velvet curtains, as a theater stage would. A lord pranks a drunk tailor named Sly by treating him as a nobleman who has been asleep for fifteen years. The servants, hiding their laughter, play along. Sly, thinking he is a nobleman, meets a page posing as his wife, who persuades him to watch a comedy instead of joining him in bed. Shakespeare’s play illustrations pose questions for historians: Do they reflect stage productions accurately or influence them?

Black figures in British Art

In the original painting, Robert Smirke included the portrayal of a black servant, standing taller than the surrounding highborn gentlemen, holding a pitcher of what could possibly be water or coffee. Between the 16th and 17th centuries, Black servants (most were slaves at the time) were seen as symbols of wealth, status and refinement within British aristocratic homes. By the late 18th century, slavery in Britain became increasingly rare, resulting in legal and social opposition after 1772. In earlier 18th century portraits, Black servants, often boys or young men in exotic attire (often a mix of African, Indian and Arab influences as we see in this piece), were depicted in affluent domestic settings, alongside commodities like coffee, chocolate, or tea from the West Indies. Unlike the overexaggerated racist depictions common in America, European artists often portrayed Black figures with individuality and dignity. It is important to call out how these images still reflected underlying themes of objectification and racial hierarchy.

Robert Smirke: Taming of the Shrew. Introduction. Scene ii. A room in the Lord’s house. – Sly with Lord & attendants. Engraved by Robert Thew, published Jan 4, 1794.

“SLY. Am I a lord? And have I such a lady?

Or do I dream? Or have I dream’d till now?

I do not sleep: I see, I hear, I speak:

I smell sweet savours, and I feel soft things:-

Upon my Life, I am a lord indeed;”

John Opie: Winter’s Tale. Act II, scene iii. Engraved by Jean Pierre Simon, published June 4, 1793. Location of the original painting: Northbrook Sale, Stratton Park, November 27, 1929

“LEO. It shall be possible: Swear by this sword,

Thou wilt perform my bidding.

ANT. I will, my lord.

LEO. Mark, and perform it; (seest thou?) for the fail

Of any point in’t shall not only be

Death to thyself, but to thy lewd-tongued wife;

Whom for this time, we pardon”

History painter John Opie, once hailed as “The Cornish Wonder” and even compared with Caravaggio, surprised viewers at the Shakespeare Gallery with his dramatic scenes and realistic approach, as if the scenes were taken straight from the stage. However, he pushed the dramatic action and emotion beyond the usual limits. In this scene, Leontes’ irrational rage is depicted as militant. Following the text, Opie shows Leontes holding a sword for Antigonus to wear on while pointing to a vulnerable infant. Opie’s choice of depicting his lighting highlights the metal armor and vulnerable baby. Leontes is shown front and center and gives off such stage quality that it looks like a study of stage action.

John Opie: Second Part of King Henry the Sixth. Act I, scene iv. Mother Jourdain, Hume, Southwell, Boldingbroke & Eleanor. Engraved by Charles Gautheir Playter and Robert Thew, published Dec 1, 1796

“SPIR. Adsum.

M. JOURD. Asmath.

By the eternal God, whose name and power

Thou tremblest at, answer that I shall ask;

For till thou speak thou shalt not pass from hence.

SPIR. Ask what thou wilt: – That I had said and done.”

Opie was said to be influenced by scenes of witchcraft by Salvator Rosa and Jacob de Gheyn. In addition to scenes like Talbot’s interview with the Countess of Auvergne and the Temple Garden scene, Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester’s visit to Mother Jourdain is another mythical event. This visit is similar to Samuel’s visit to the Witch of Endor, as both are considered illegal and treasonous. Opie’s depiction of Mother Jourdan at her cauldron is more horrifying than Reynolds’. She holds a knife used to draw an infant’s blood, a key ingredient for her spell, and the dead baby lies at her feet among scattered human bones. The fiend points across the cauldron, revealing that “The Duke yet lives that Henry shall dispose”.

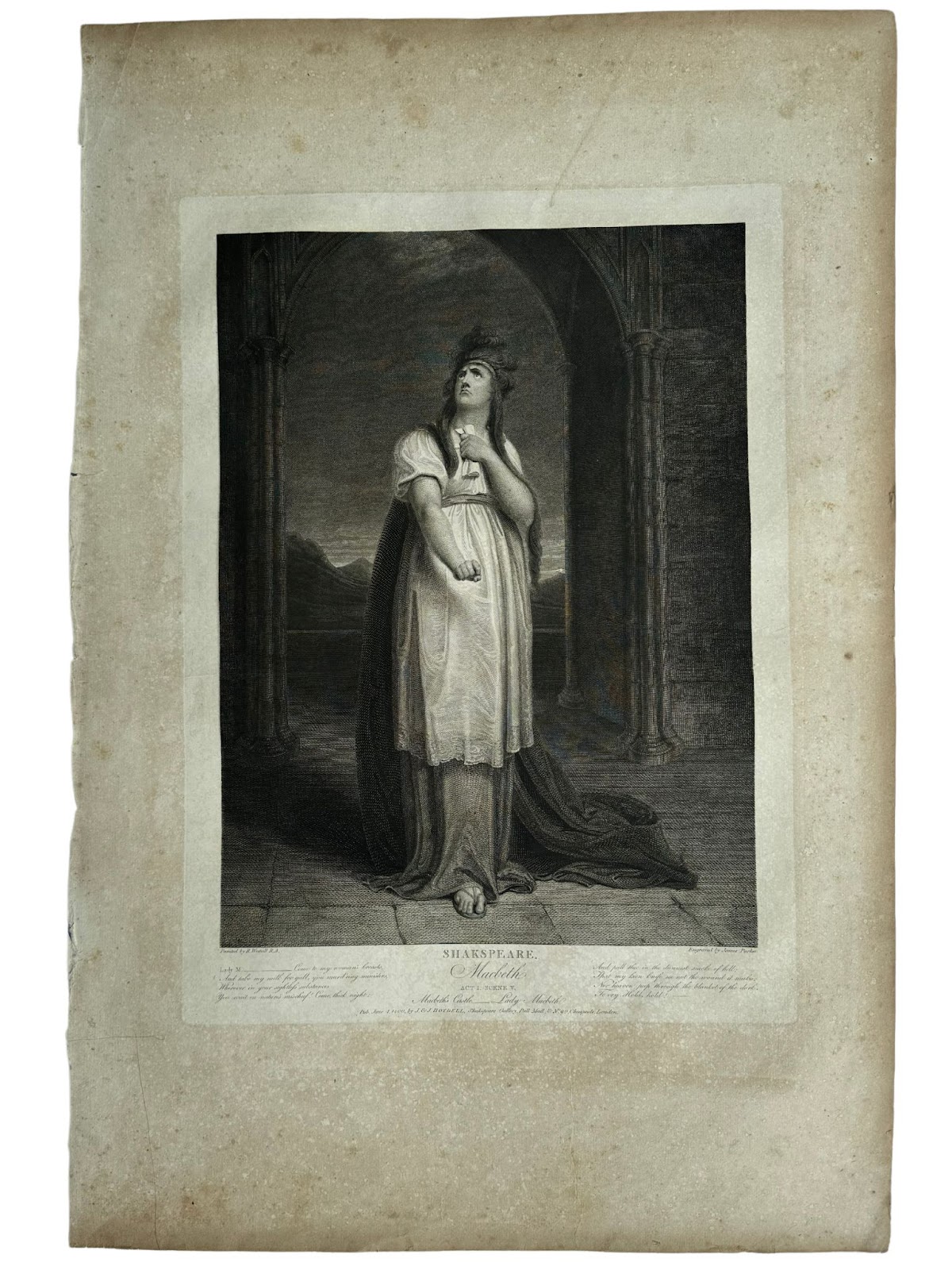

Stage Actors/Celebrities

Westall’s painting shows Lady Macbeth preparing to murder King Duncan. Despite Boydell’s instruction to avoid stage depictions and focus on historical imagination, artists often used famous actors as models. Sarah Siddons, portraying Lady Macbeth from 1785 to 1812, often evoked intense reactions. Her dramatic light and clenched fist aimed to provoke fear, reflecting the 18th-century actors’ study of antique sculptures. Siddons’ influential performance shaped discussions for decades, embodying power and passion, as seen in Westall’s painting where her clenched fist symbolizes intense passion.

Henry Fuseli (Johann Heinrich Fussli, 1741-1825) completed nine large paintings for the Shakespeare Gallery, but six are missing or destroyed and only known through the surviving engravings.

Richard Westall: Macbeth. Act I, scene v. Macbeth’s Castle – Lady Macbeth. Engraved by James Parker, published June 4, 1800.

“LADY M. Come to my woman’s breasts,

And take my milk for gall, you murd’ring ministers,

Wherever in your sightless substances

You wait on nature’s mischief! Come, thick night;

And pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell;

That my keen knife see not the wound it makes;

Nor heaven peep through the blanket of the dark,

To cry, Hold, hold!-”

Johann Henrich Fuseli: Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. Act I, scene iv. The Platform before the Palace of Elsineur. – Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus and the Ghost. Engraved by Robert Thew, published September 29, 1796.

“HAM. Still am I call’d. – unhand me gentlemen;

[Breaking from them.

By heaven, I’ll make a Ghost of him that lets me:-

I say, away: – Go on, – I’ll follow thee.

Hamlet struggles against Horatio’s hold, similar to Banquo’s pose from Macbeth. The Ghost, depicted in armor, is vividly real with moonlight radiating through its eyes and beard.

Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff is a comic character of Shakespeare’s plays. A fat, vain, and boastful knight, he spends most of his time drinking at the Boar’s Head Inn with petty criminals, living on stolen or borrowed money. The Shakespeare editor Nicholas Rowe wrote in 1709 that Queen Elizabeth liked Falstaff’s character so much in the Henry IV plays that she asked Shakespeare to write more plays with Falstaff in them. As a result, Falstaff appears in many of the paintings and engravings of the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. This scene shows Sir John Falstaff at the Boar’s Head Tavern, run by Mistress Quickly, before heading north to recruit soldiers. Smirke’s Falstaff is a corrupt soldier, while Fuseli’s is self-indulgent and passive, waiting for pleasures to come to him. Doll Tearsheet, young and beautiful, is curled up on his lap. Falstaff argues with Doll and Pistol and makes rude comments about Prince Henry and Edward Poins, not knowing they are spying on him in the background, disguised as barmen. Fuseli’s theatrical style is seen in the costumes, composition, and décor inspired by London stage performances. He emphasizes Falstaff’s comic role by contrasting his large presence with Tearsheet’s delicate appearance, highlighting Falstaff’s bodily desires.

Johann Heinrich Fuseli: Second Part of King Henry the Fourth. Act II, scene iv. Doll Tearsheet, Falstaff, Henry, & Poins. Engraved by William Satchwell Leney, published March 25, 1795.

Dol. I’faith, and thou followd’st him like a church.

Thou whoreson little tidy Bartholomew boar-pig,

when will thou leave fighting o’days, & foining o’nights,

& Begin to patch up thine old body for heaven.”

James Durno: Merry Wives of Windsor. Act IV, scene ii. A room in Ford’s House. – Falstaff in women’s clothes led by Mrs Page. Engraved by Thomas Ryder, published June 4, 1801. Location of the original painting: Soane Museum, London.

“FORD. I’ll prat her: – Out of my doors, you witch!

[beats him.] you hag, you baggage, you poecat, you ronyon!

Out! Out! I’ll conjure you, I’ll fortune-tell you.

[Exit Falstaff.]

Apart from Smirke’s depictions of “The Seven Ages”, The Merry Wives of Windsor had the most illustrations of any play in the Gallery, with five folio plates and two quarto plates. This is due to the character Falstaff’s popularity. Shakespeare wrote this comedy for Falstaff at Queen Elizabeth’s request to see Falstaff in love. In Durno’s painting, he depicts Falstaff in a busy scene, which shows ten characters, including Falstaff disguised as a woman.

James Durno: Second Part of King Henry the Fourth. Act III, scene ii. Justice Shallow’s Seat in Gloucestershire- Shallow, Silence, Falstaff, Bardolph, Boy, Mouldy, Shadow, Wart, Feeble, & Bull-calf. Engraved by Thomas Ryder, published Dec 1, 1798. Location of the original painting: Sotheby’s october 14, 1953.

“FAL. Come manage me your caliver;

So, very well, go to,

Very good, exceeding good. O give me always a little

Lean, old, chopp’d bald shot. Well said, i’faith,

Wart, thou’rt a good scab, hold, there’s a teter for thee.”

Critics complained that in this scene, Durno did not capture the comedy of the scene, only Falstaff’s belly. In Shakespeare’s play, Falstaff’s recruitment scene is filled with witty dialogue, but this doesn’t seem to be captured here in Durno’s depiction as all we see is Falstaff’s pointing finger, Shallow’s whispering, and Bardolph accepting a bribe.

Robert Smirke: First Part of King Henry the Fourth. Act II, scene iv. The Boar’s Head Tavern. – Prince Henry, Falstaff, Poins, & c. Engraved by Robert Thew, published June 4, 1796. Location of the original painting : Bob Jones University, Greenville, South Carolina.

FAL. Shalt I? content:_____This chair shall be my state,

this dagger my sceptre, and this cushion my crown.

Here we see Sir John Falstaff sitting at a table with one leg on a stool. He’s holding a dagger in one hand and his cap in the other. He orders his favorite drink, ‘Sack’, and brags about his bravery in the last battle. Peto, Gadshill, Bardolph, Poins, and the Prince of Wales listen to him. When Falstaff exaggerates too much, Prince Henry angrily calls out his lies. Then the Sheriff arrives to question Falstaff and his friends about a robbery. The Boar’s Head Tavern in Eastcheap, run by Mistress Quickly with help from the barman Vintner, Francis, and other servants, is one of Falstaff’s favorite spots.

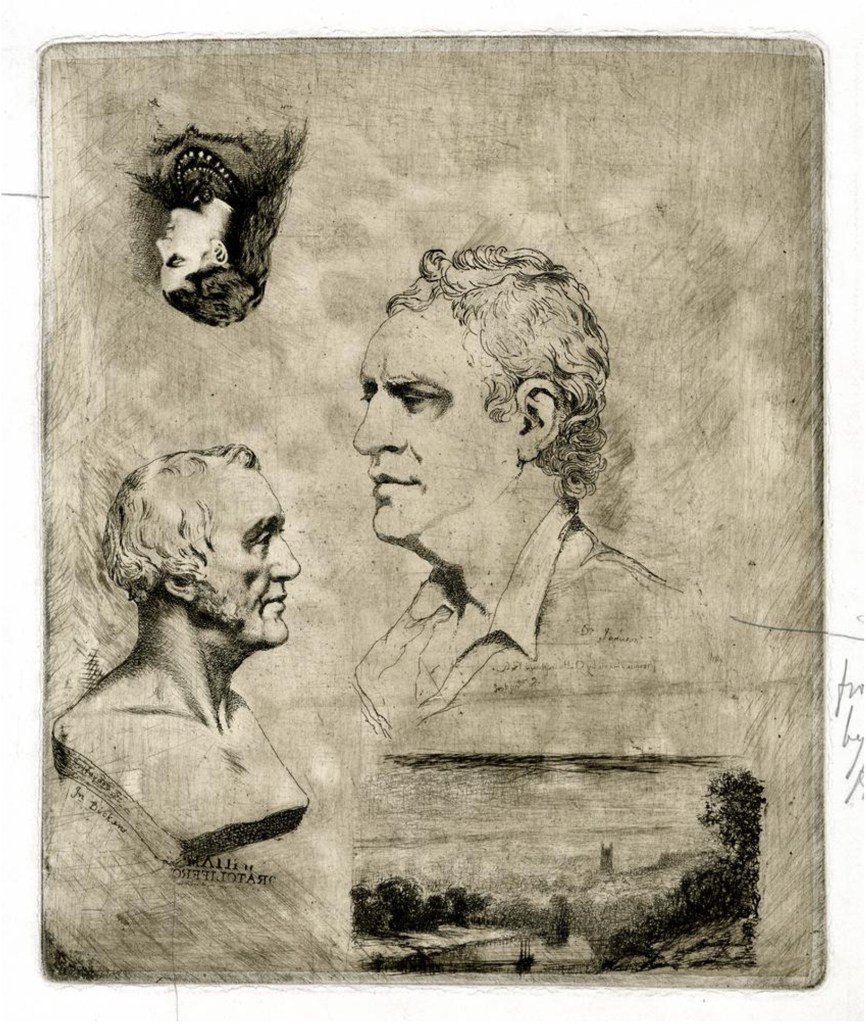

Sir Joshua Reynolds: Second Part of King Henry the Sixth. Act III, scene iii. [Death of Cardinal Beaufort] Engraved by Caroline Watson, published August 1, 1792. Location of the original painting: Petworth, replica: Stratford-on-avon

“WAR. See, how the pangs of death do make him grin!

SAL. Disturb him not; let him pass peaceably.

K. HENRY. Peace to his soul, if God’s good pleasure be! –

Lord Cardinal, if thou think’st on heaven’s bliss,

Hold up thy hand, make signal of thy hope. –

He dies, and makes no sign: – O God, forgive him!”

Rembrandt was known to inflict pain upon himself to sketch his face in a grimace, showing the importance of studying natural expressions of emotion. Viewers at the Shakespeare Gallery were disturbed by Reynold’s use of a grimace in his painting of Cardinal Beaufort on his deathbed, with a demon’s face hovering in the corner by his bedside, known to make the entire scene grotesque. In response to the criticism, Boydell had the demon removed in later engravings.

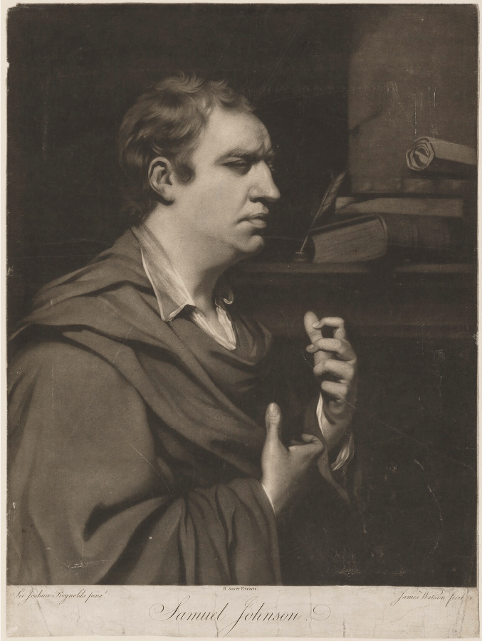

Caroline Watson engraved the painting, and she was known as the first professional female engraver in the UK and Engraver to Queen Charlotte. She started her career under the tutelage of her father, printmaker James Watson, and worked as a portrait artist for royalty and then moved onto creating aquatints for works by Italian-English artist and educator Maria Cosway.

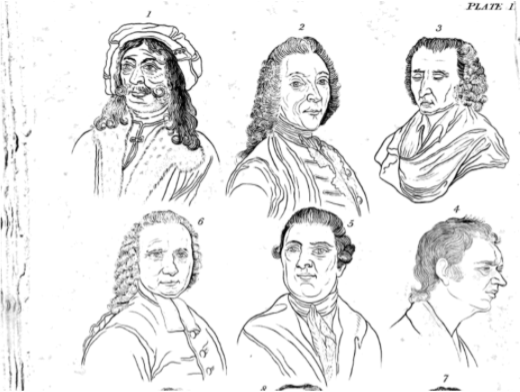

Robert Smirke and The Seven Stages

“The Seven Ages of Man” is a monologue from Shakespeare’s play As You Like It, ACT II, scene vii. In this passage, the character Jaques reflects on the stages of human life, describing them as a series of acts in a play. The seven stages as he outlines are: 1. Infant 2. Schoolboy 3. Lover 4. Soldier 5. Justice 6. Pantaloon 7. Second Childishness. I own stages 4-7.

Smirke turns the seven stages into a series of pleasant, genre scenes with costumes from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Smirke’s focus is on illustrating sentimental, moral scenes, not on theater or drama.

The Fourth Age (Manhood): In the previous age, the young man was consumed by love. In this age, the mature man is driven by ambition, seeking reputation.

Robert Smirke: As You Like It. Act II, scene vii. The Seven Ages. Fourth Age. Engraved by John Ogborne, published June 4, 1801.

Jaq. __________ Then, a soldier;

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like a pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth.

Robert Smirke: As You Like It. Act II, scene vii. The Seven Ages. Fifth Age. Engraved by Jean Pierre Simon, published June 4, 1801.

“Jaq._____ And then, the justice;

In fair round belly, with good capon lin’d,

With eyes severe, and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances,

And so he plays his part.”

The fifth age is middle age. Ambition has paid off, and now our man is a judge with a “fair round belly.” He sternly delivers justice to a sentenced couple. Shakespeare says, “And so he plays his part,” referring back to the famous lines, “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players.” In a way, the judge is as trapped as those he convicts. This scene shows a judge sentencing a young couple. On the left, a wealthy-looking man (probably the plaintiff) sits with a sleeping dog at his feet. On the right, the young man and woman (the offenders) listen to the verdict. The judge, a middle-aged man, is in the center of the engraving. People are watching the trial from both sides of the courtroom.

Robert Smirke: As You Like It. Act II, scene vii. The Seven Ages. Sixth Age. Engraved by William Satchwell Leney, published June 4, 1801.

Jaq. ________ The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper’d pantaloon;

With spectacles on nose, and pouch on side;

His youthful hose well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again to childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound:

In the sixth age, middle age turns into old age, with “Shrunk shank.” An unfortunate family asks for help at his door but is rudely sent away by him and his dog.

Robert Smirke: As You Like It. Act II, scene vii. The Seven Ages. Seventh Age. Engraved by Jean Pierre Simon, published June 4, 1801.

Jaq._____ Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness, and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

‘The Seventh Age’ (Old Age) is the last and cruelest stage. It’s like a second childhood. At the feet of the frail old man, a young boy plays with a house of cards. In the background, a nurse is asleep. The paintings on the walls show the effects of time. Life ends brutally in “mere oblivion; Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” In this scene, the artist shows a drowsy, weak old man wrapped in blankets as the main character, representing the seventh age. The old man sits by a dark, cold fireplace, unaware of the paintings, the sleeping woman, or the child playing on the floor. To his right is a chest of drawers with a bowl for porridge, a mug for hot milk, bottles, and other medicines for his pain. A pair of crutches leaning against the chest shows his lack of mobility.

Conclusion

By employing some of the most renowned British artists of the late 18th century and elevating British art during a politically tumultuous time, The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery influenced the visual representation of Shakespeare’s works for generations. The success and visibility of the engravings influenced subsequent artistic representations of Shakespearean scenes and were reproduced in various forms including books, prints and later theatrical productions. Although the gallery itself did not survive long-term financial challenges and eventually closed in the early 19th century, its impact on both art and the popularization of Shakespeare remains notable.

References

Marketing Shakespeare: the Boydell Gallery, 1789–1805, & Beyond – Folgerpedia https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Marketing_Shakespeare:_the_Boydell_Gallery,_1789%E2%80%931805,_%26_Beyond?_ga=2.108326020.78832302.1720647577-570080926.1720647577

Burwick, Frederick and Pape, Walter. (1996). The Boydell Shakespeare Gallery. Peter Pomp.

Dias, Rosie. (2013). Exhibiting Englishness: John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery and the Formation of a National Aesthetic. The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

Abusing Power: The Visual Politics of Satire

Abusing Power: The Visual Politics of Satire